Early Tinkerers of Electric Tattooing

Researched and written by Carmen Forquer Nyssen

Early Tinkerers of Electric Tattooing

Tattoo Machine History: Invention of Electric Tattoo Machines

Researched & Written by Carmen Forquer Nyssen

Although a definitive history is impossible to capture, this essay offers groundbreaking insight into the emergence of electrical tattooing. It required years of research and synthesizing to formulate.

“The first electric tattoo machine was invented in New York City by Samuel F. O’Reilly, and patented December 8, 1891 (US Patent 464, 801). Adapted from Thomas Edison’s 1876 rotary operated stencil pen (US Patent 180,857), this machine revolutionized the trade of tattooing, bringing it into a more modern age.”

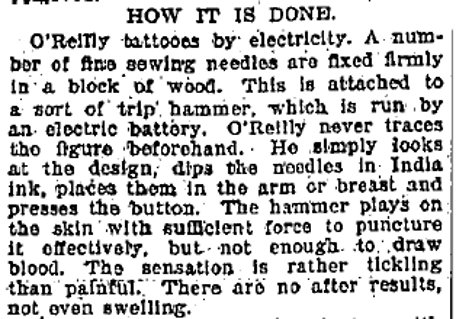

O’Reilly Tattooing. Ev’ry Month Magazine, Oct 1899. Pg 5. Print.

This standard blurb has neatly summarized 1800s American tattoo machine history in countless books and articles. But it falls short of the bigger picture. As we’re about to learn here, the story of how the electric tattoo machine came to be isn’t that straightforward. It has quite a few twists and turns.

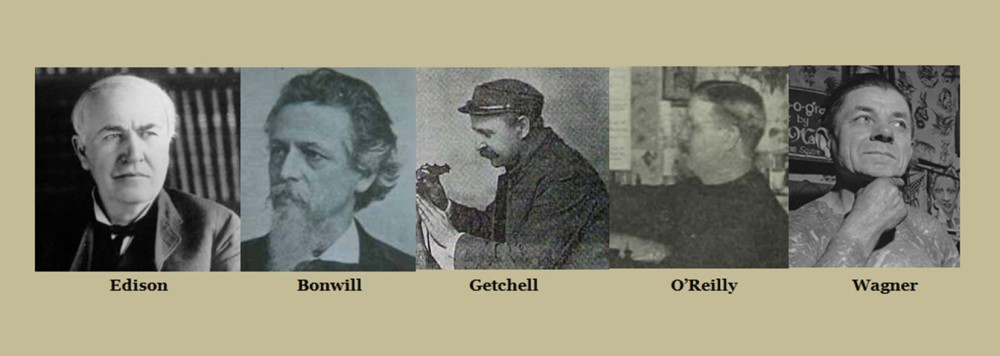

Samuel F. O’Reilly (1854-1909) is the usual character that comes to mind when speaking of early tattoo machines. O’Reilly was born in New Haven, Connecticut to Irish immigrants Thomas O’Reilly and Mary Hurley. He first appears in Brooklyn City Directories in 1886, along with his brothers John and Thomas. Though he isn’t on record as a tattoo artist until 1888, by then he’d made a name on the New York Bowery as the Chatham Square Museum’s “celebrated tattooer.” Just a few years later —in 1891 —he secured the very first tattoo machine patent based on Thomas Edison’s 1876 rotary operated stencil pen patent (technically a rotary-electromagnetic coil hybrid).

The Edison pen was a handheld, reciprocating, puncturing device designed for making paper stencils. Its form and function made it an apt candidate for tattooing. Edison actually patented several stencil pens in the 1870s that might have been adapted for tattooing had they been manufactured. In fact, so evident was the tattooing potential of his inventions, it was recognized almost right from the start.

In 1878, nearly thirteen years before O’Reilly’s patent was in place, an anonymous contributor (alias “Phah Phrah Phresh”) wrote a letter to the editor of the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper, proposing that Edison’s recently published stencil pen patent could be transformed into a tattooing machine with just a few minor adjustments. He (or she) dubbed this conceptual machine the “teletattoograph.”

Were tattooers using electric tattoo machines by 1878 then? The Brooklyn Eagle letter certainly seems a game-changer. Logic follows that once an electric tattoo machine was envisioned, it was only a matter of time before one was made. But we shouldn’t draw any conclusions just yet. As it stands now, there’s no proof tattooers were working with electric tattoo machines this early on. Until the late 1880s, newspaper reports only reference hand tools.

That being said, electric tattooing didn’t begin with O’Reilly’s 1891 patent either. It was introduced at least several years prior. The latter half of the 1880s may have been the breakthrough period. Existing evidence points to electric tattooing as a more recent phenomenon then and additional reports show substantial progression from that time forward.

Accessibility was no doubt a major factor. This period was marked by a phase of rapid advancement in electrical apparatuses. By the mid to late 1880s, electric motors had reached phenomenal heights, and a greater range of electrically driven appliances became available to the general public. As advertised in an 1887 promotional article for an electrical exhibition in New York City, an upward of 10,000 electric devices had been introduced since the last show in 1884, including everything from small tools and surgical instruments to appliances for various arts and general conveniences.

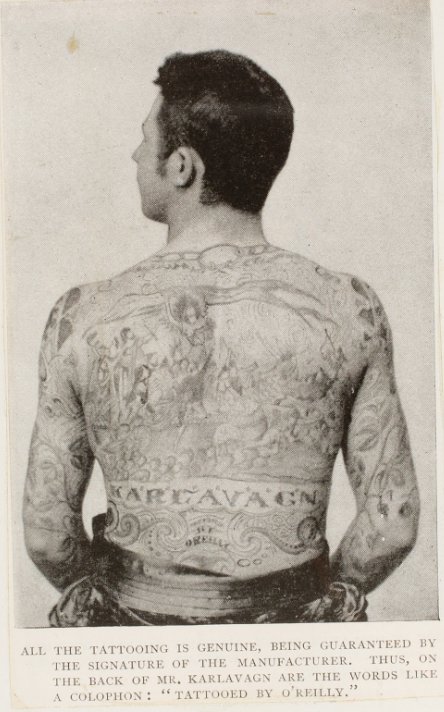

Karlavagn, Tattooed by O’Reilly. The Illustrated American. Nov 8, 1890. pg. 365. Print.

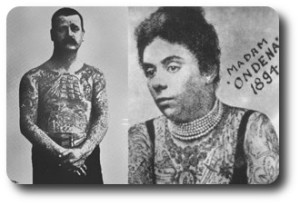

O’Reilly confirmed in an 1897 interview that he developed his first machine right when electrical gadgets came into general use. Though an 1888 New Rochelle Pioneer newspaper article described him tattooing with the traditional “needles in a bunch,” technology was on the horizon. In 1889 and 1891 respectively, purported O’Reilly creations Tom Sidonia and George Mellivan made a sensation on the dime show stage exhibiting their “electrically tattooed” bodies. Also, in 1890, “electrically tattooed” man, George Kelly (aka Karlavagn) took to the stage sporting the telltale lettering on his back “Tattooed by O’Reilly.”

Tattooed man and tattoo artist, “Professor” John Williams, had apparently picked up electric tattooing in this period as well. Throughout the 1880s, Williams performed on the United States dime show circuit at venues such as the World’s Museum in Boston and Worth’s Museum in New York. Sometime between December of 1889 and January of 1890, he made his way to England, where he awed museum audiences by tattooing his wife, Madame Ondena, on stage with a “new method” he said was discovered by himself and “Prof. O’Reilly of New York.” As he assured in a January 11, 1890 London Era advertisement, his act was “startling, astonishing, interesting, and novel, and lively” and “a perfectly safe and painless performance.”

Within another year’s time, electrically tattooed attractions seem to have become a trend in America. In January of 1891 —six months before O’Reilly applied for his patent —the New York Dramatic Mirror printed the following:

“What is announced as the “Kalamazoo electric tattooed man is the latest novelty in freakdom.”

If we can also take the New York Herald at its word, electric tattooing was well underway among the dime show crowd. In March of 1891 —still months prior to O’Reilly’s patent submission in July —the Herald reported that tattooed performers had become quite plentiful, because of the introduction of electric tattoo machines.

Even the wording of O’Reilly’s patent application —that he had invented “new and useful Improvements in Tattooing-Machines” —suggests electric tattoo machines had already been in use. The question is ….. what types of machines were tattoo artists working with?

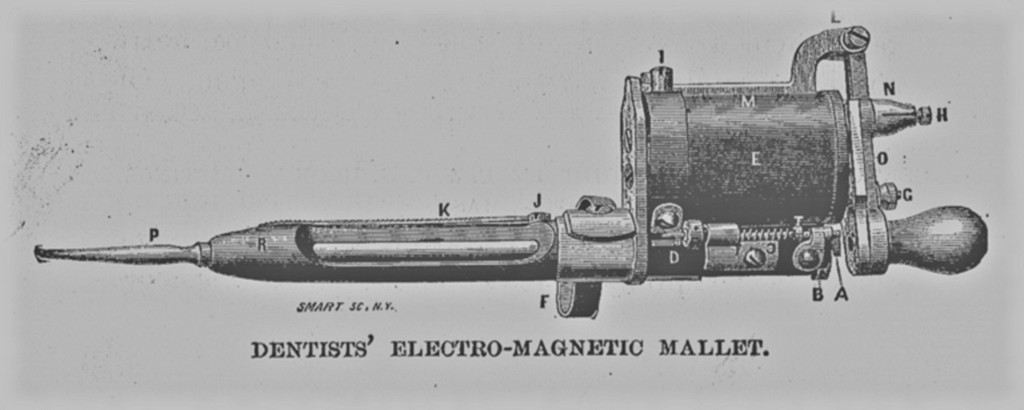

Dental Pluggers:

This is perhaps the biggest revelation. The Edison pen probably wasn’t the first or only go-to device. O’Reilly’s first pre-patent machine was not an Edison pen. It was a modified dental plugger (also referred to as a mallet or hammer) —a handheld tool with reciprocating motion used to impact gold in cavities. A reporter for the Omaha Herald wrote about it in June of 1890, describing it as “…a little electric machine, which caused a small cable of woven wire to revolve something in the manner of a drill which dentists use in excavating cavities in teeth…” As with Edison’s stencil pen, a variety of dental pluggers were invented in the 1800s that are believed to have been modified for tattooing. Several such dental pluggers are archived in modern day tattoo collections.

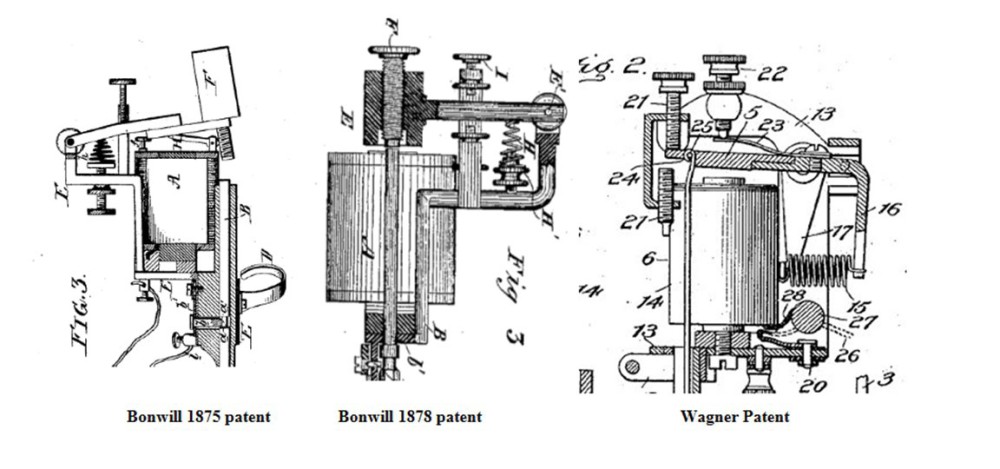

An industrious dentist and inventor named William Gibson Arlington Bonwill (1833-1899) is credited with inventing the first electromagnetically operated dental plugger, and in so doing, the first electrically operated handheld implement. Bonwill’s idea was born in the late 1860s after observing the electromagnetic coils of a telegraph machine in operation. His first two patents were filed in 1871 (issued October 15, 1878 -US Patent 209,006) and in 1873 (issued November 16, 1875 -US Patent 170,045). Like today’s tattoo machines, Bonwill’s devices operated by way of two vertically-positioned electromagnetic coils; except offset from the frame. Additional features were stroke adjustment, an on/off slider, and a stabilizing finger slot.

Bonwill achieved wonders with his invention. His goal had been to design a device “manipulated as readily as the usual hand tools,” geared toward optimum handheld functionality. Bonwill took great care in considering the shape of the frame, the weight of the machine, and its mechanical efficiency, via size and placement of the coils in relation to the frame, armature, and handle. In the process, he also greatly improved upon both the electro-magnet and armature.

As with most newborn inventions, Bonwill’s machine wasn’t perfect. It underwent many immediate improvements. But as the first electrically operated handheld implement, it was an outstanding breakthrough —for many fields. It was so exceptional Bonwill was awarded the Cresson Medal, the highest honor of the Franklin Institute of Science. (George F. Green received a patent around the same time as Bonwill. But Bonwill’s prototype machines and his ideas were introduced to the dental community years prior. His invention was recognized among peers as the first truly “practicable model”).

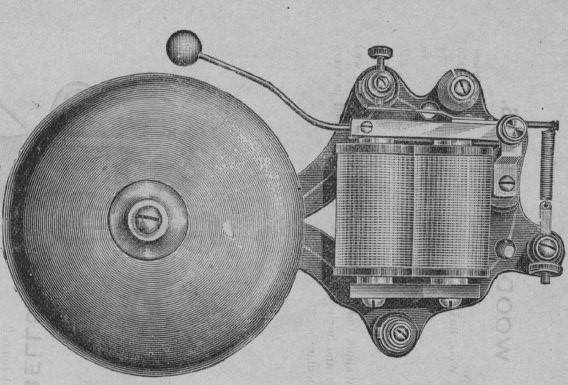

Dentist’s Electromagnetic mallet. Ingram, J.S. The Centennial Exposition. Hubbard Bros., 1876. pg. 300. Print. Collection of Carmen Nyssen.

__

According to dental journals, the S.S. White Dental Manufacturing Company began producing and marketing Bonwill’s device, “The Bonwill Electro-magnetic Mallet –With Improvements by Dr. Marshall H. Webb,” in the mid-1870s to mid-1880s period. S.S. White, then the largest dental manufacturing company in the world, manufactured several similar dental pluggers, including the G.F. Green version. Although cylindrical shaped (with a spring coil in the core ) and rotary operated dental pluggers later came into play, given the description of the visible coils on O’Reilly’s machine, there’s little chance it was adapted from anything other than the Bonwill or Green model, or a like machine. It only makes sense. The engineering of these types of dental pluggers was most similar to modern day tattoo machines. For this reason, they happen to be the ones highly sought after by tattoo collectors. (See Kornberg School of Dentistry’s online database for examples of various dental pluggers).

Bonwill was fully aware his invention was transferable to other fields. As he boldly asserted in patent text, “My improved instrument, although especially adapted for tooth filling, can be applied to the arts generally, wherever power by electricity is needed or can be used for actuating a hammer.” A report on exhibits at the Franklin Institute’s 1884 electrical exhibition noted that Bonwill’s machine had been used in dentistry, as a sculpting device, an engraving device, and notably, as an autographic pen.

Interestingly, years earlier in an 1878 interview, Bonwill claimed that Thomas Edison borrowed the principles of his dental plugger when developing the 1877 electromagnetic stencil pen (US Patent 196,747) —also a handheld device with vertically-positioned coils. Bonwill’s assertion is worth mentioning, since it’s been said that Edison’s invention was the inspiration for Charlie Wagner’s 1904 tattoo machine patent (US Patent 768,413). Though it’s typically believed that Edison stumbled on the idea for a handheld stencil pen while experimenting with telegraphic communication, it’s certainly plausible that he was influenced by Bonwill’s invention. Bonwill had displayed his dental plugger at exhibitions and conferences since the early 1870s. As noted in his 1874 pamphlet A Brief History of the Electro-magnetic Mallet, a prototype had already been on trial in dental practices for several years. While Edison, a former telegraph operator, was well-versed in electromagnetic technology, he and partner, Charles Batchelor, didn’t commence work on their various handheld devices until July of 1875. (This was an array of rotary and electromagnetic stencil pens first patented in the United Kingdom (UK 3762) on October 29, 1875. See Edison papers, Rutgers Museum).

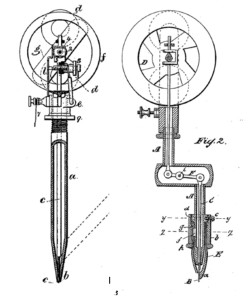

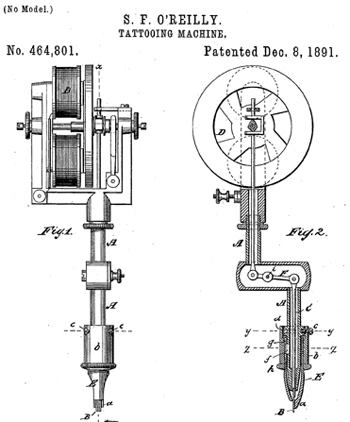

O’Reilly’s 1891 Patent:

Backstory aside, it’s clear that inventors like Bonwill, Green, and Edison —who made the extraordinary, inventive leap of converting an electromagnetic coil mechanism into a practical handheld instrument —greatly influenced the development of electric tattoo machines. Unnamed others unquestionably played a role as well. In the 1870s, electric handheld implements were, as of yet, novelties. When tradesman and practitioners began using these tools in a professional capacity, they encountered limitations. Efforts to resolve shortcomings led to further discovery and innovation. When tattoo artists began modifying the same electric devices for their own purposes, it would have produced a whole new wave of findings.

At this point, the full range of machines available to early tattooers isn’t known. But dental pluggers and Edison’s rotary pen (the only known Edison pen manufactured) were conceivably at the top of the list. In an 1898 New York Sun interview, O’Reilly said he experimented with both before settling on his patent design. With his dental plugger machine, he claimed, he could tattoo a person all over in less than six weeks. But there was room for improvement. Discussing the trial-and-error process, he said he first tried the dental plugger, then an Edison pen, but each was “too weak;” finally, after many trials, he “made a model after his own idea, had it patented, and got a skilled mechanic to build the machine.”

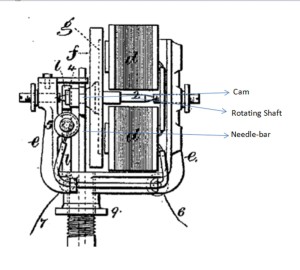

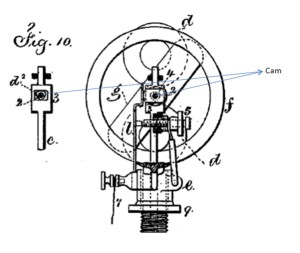

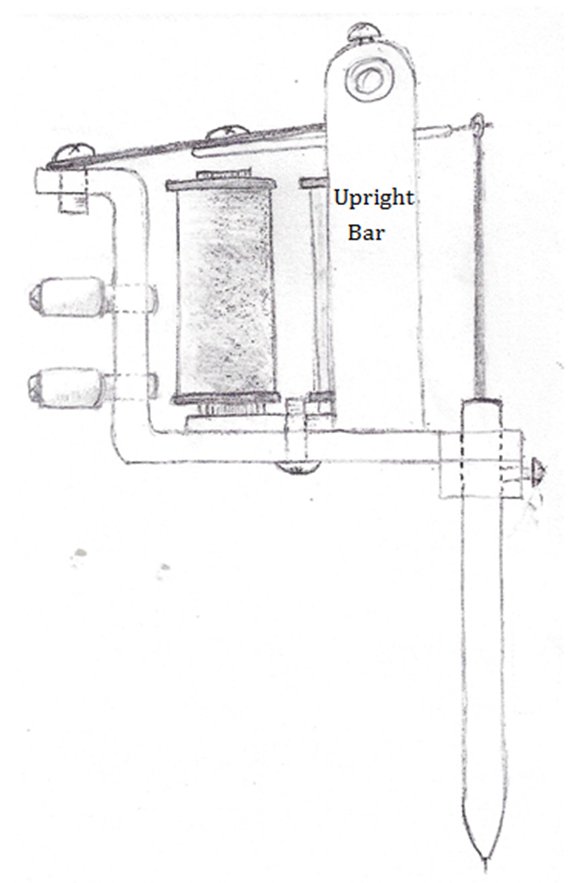

O’Reilly’s patent machine, in essence an Edison pen, was modified by adding an ink reservoir, accommodations for more than one needle, and a specialized tube assembly system meant to solve the “weakness” issue of his previous machines. Like the original Edison pen, the reciprocating action of O’Reilly’s machine, was actuated via an eccentric (cam) working on the top of the needle bar. But instead of a straight stylus, the tube encasing the needle bar (also the handle) was constructed with two 90 degree angles, while the needle bar inside was segmented with pivots. This set up allowed for a lever and fulcrum system that further acted on the lower end of the needle bar and theoretically served to lengthen the stroke/throw of the needle.

__

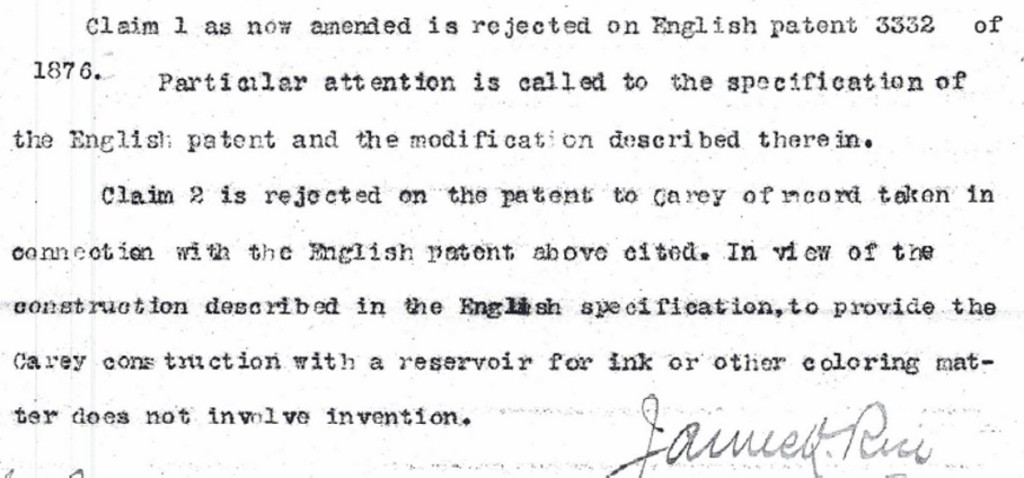

As it turns out, the patent office didn’t consider O’Reilly’s “improvements” all that innovative. They denied his application at first. Not because his invention was too similar to Edison’s 1876 rotary device, but because it bore likenesses to Augustus C. Carey’s 1884 autographic pen patent (US Patent 304,613). They denied it a second time citing British patent UK 3,332 (William Henry Abbott’s sewing machine patent), perhaps owed to its reciprocating needle assembly. Rejection notes clarify that in connection with the UK patent it would not have involved invention to add an ink reservoir to the Carey pen. (Carey’s patent already included specifications for a type of ink duct).

National Archives at Kansas City. Application. Tattooing Machine. Samuel F. O’Reilly, assignee. Patent 464801. 8 Dec. 1891. Print.

__

Due to the crossover in invention, O’Reilly had to revise his claims several times before his patent was granted. This actually happened frequently. Patent law permits inventions based on existing patents. But applicants have to prove their creation is novel and distinct. This can be tricky and might be one reason more of the early tattoo artists didn’t patent their ideas —though for all we know a few might have tried and failed. (Unfortunately, all pre-1920s abandoned patent applications have been destroyed).

—

Tom Riley of England:

According to legend, twenty days after O’Reilly obtained his rotary patent in the U.S., England’s Tom Riley allegedly obtained a British patent for a single-coil machine. However, while Riley could have invented such a device, he didn’t patent it. A British patent isn’t on file. More likely, the story has been confused over the years. Pat Brooklyn —in his interview with Tom Riley entitled Pictures on the Skin —discusses a single-coil machine Riley was tattooing with in 1903, but doesn’t mention a patent for this machine at all. What he does inform is this: “The electric-needle was invented by Mr. Riley and his cousin, Mr. S.F. O’Riley [sic]…and was patented by them on December 8, 1891, although it has since had several alterations and improvements made to it.”

Since we know Riley wasn’t O’Reilly’s co-patentee, his claims in this interview were obviously embellished. Once the story was printed though, it was probably passed on and muddied with each re-telling. It very well could have inspired the comments in George Burchett’s Memoirs of a Tattooist; that Riley obtained a British patent on December 28, 1891, which improved on O’Reilly’s patent by adding six needles. The first British tattoo machine patent was actually issued to Sutherland MacDonald on December 29, 1894 (UK 3035) (note the similarity of the month and day with the alleged Riley patent). Sutherland’s machine was cylindrical shaped with the needles moving through the core of the electromagnetic coils inside, quite similarly to some of the cylindrical shaped dental pluggers and perforating pens of the era.

—

Professor Feggetter:

Considering the problems O’Reilly encountered with his patent, it’s possible he enlisted help. The patent process entails consulting trusted experts and O’Reilly himself acknowledged that a “skilled mechanic” built his patent model. This might have been the machinist, inventor, and mechanical illusionist from England, named John Feggetter Blake, or “Professor Feggetter” to dime museum audiences. After arriving in the U.S. in 1872, Blake obtained numerous patents for his inventions, the first being a Three Headed Songstress illusion sponsored by Bunnell’s Dime Museum of New York. And, he was acquainted with O’Reilly.

NARA; Washington, D.C.; Index to Petitions for Naturalizations Filed in Federal, State, and Local Courts in New York City, 1792-1906. “40 South” was the location of Edwin Thomas’ tattoo shop before he was imprisoned for shooting his ex-girlfriend in 1890.

Not only did Blake’s patent lawyers (John Van Santvoord and William Hauff) submit O’Reilly’s initial patent claim in July of 1891, but also, in October, not long after his patent claims were initially denied, O’Reilly signed as a witness on Blake’s naturalization application.

Although it’s unclear whether Blake was involved in the development of O’Reilly’s invention, it’s striking that many of his inventions operated via pivots, levers, and fulcrums, much like O’Reilly’s tube assembly. Also, in the years just following O’Reilly’s patent Blake began patenting a series of electromagnetic contact devices.

Adding to intrigue, Blake was associated with John Williams, the British dime show tattooer who claimed both he and O’Reilly discovered a “new method” of tattooing several years earlier. The two had headlined together in both Boston and New York dime museums before Williams returned to his native England.

—

Whatever the link with these other men, O’Reilly holds the patent. Today, his invention is upheld as the ultimate tattoo machine of its day. As the product of dedicated trials, O’Reilly’s patent machine significantly contributed to the progression of tattoo machines. And, he certainly deserves the accolades for his efforts, especially for being the first to obtain a patent. But there’s some question as to whether he ever manufactured his invention —on a large scale anyway —or whether it was in wide spread use at any given point.

In 1893, just two years after the patent was in place, tattoo artist and vaudeville actor Arthur Birchman claimed he owned two of O’Reilly’s machines, but as he told The World newspaper reporter there were only “…four in the world, the other two being in the possession of Prof. O’Reilly…”

O’Reilly’s comments in an 1898 New York Sun interview are equally curious. He said that he had marketed a “smaller type of machine” on a “small scale,” but had only ever sold two or three of those “he uses himself.”

These snippets infer: (1) that O’Reilly didn’t necessarily produce a large quantity of the patent machines (2) that he had constructed more than one type of machine between 1891 and 1898, and (3) that the patent wasn’t the preferred tattooing device for the duration of the 1800s.

The overall implication is that O’Reilly (and other tattoo artists) continued experimenting with different machines and modifications, even after the patent was issued.

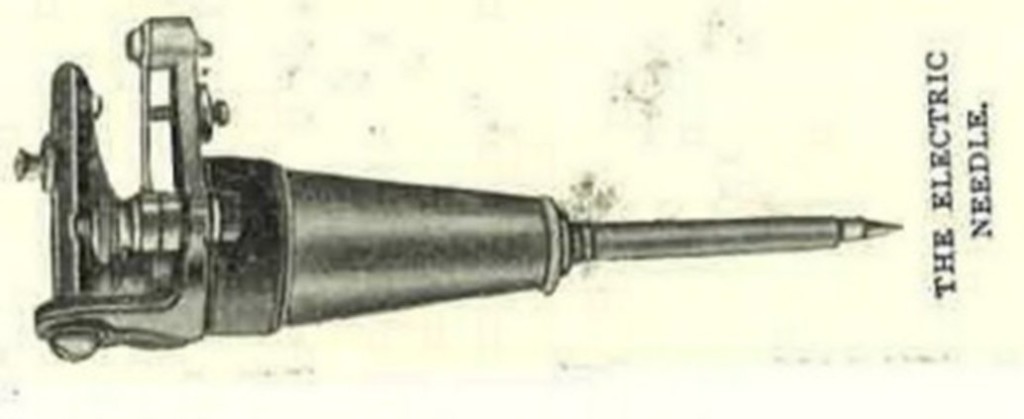

Media reports aren’t always reliable, of course, and, we’re definitely missing pieces of the puzzle. But there’s more. Additional evidence corroborates the use of a variety of tattoo machines during this era. So far, neither a working example of O’Reilly’s patent model, nor a photo of one has surfaced. But a straight-handled adaptation of the Edison pen is depicted in a number of media photos. For years, this machine has been a source of confusion. The obvious stumper is the missing crooked tube assembly. Ironically, the absence of this feature is a clue in itself. It indicates there were other ways to render the Edison pen operable for tattooing.

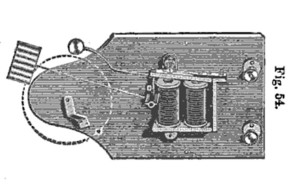

Cams:

Anyone familiar with rotary driven machines —of any sort —knows that proper functioning is contingent with the cam mechanism. The cam is a machine part that changes a machine’s motion, usually from rotary motion to reciprocating motion, by acting on a follower (i.e. needle/needle bar on a tattoo machine). Cams come in varied shapes and sizes. An apt sized/shaped cam is crucial to precise control and timing of a machine, and if damaged or changed, can alter the way a machine operates. Is it possible, then, that simply altering the cam on Edison’s rotary stencil pen could make it functional for tattooing? All the evidence suggests that it was a major part of the solution.

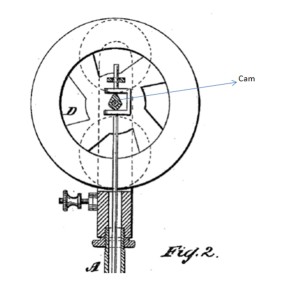

Thomas Edison paid special attention to the cam mechanism on his 1876 rotary pen. The cam was enclosed in a nook at the top of the needle-bar, where the needle bar met the rotating shaft (axis). The rotating shaft (axis) was positioned through the direct center of the cam and the flywheel. As the fly wheel revolved, and turned the rotating shaft, the cam turned with it, causing the needle-bar (follower) to move up and down.

In the text of his 1875 British patent (UK 3762), Edison noted that the cam on his rotary pens could have “one or more arms” acting upon the needle bar. A year later, when he patented the rotary pen in the U.S. (US Patent 180,857), he specified that he’d chosen to implement a three pointed-cam (three-armed or triangle-shaped cam), because it gave three up and down motions to the needle per revolution, and therefore more perforations per revolution. Perhaps, after some experimentation, Edison determined this particular cam shape best-produced the rapid movement required of his stencil pen. As we know, it didn’t work for tattooing. In O’Reilly’s words, it was too “weak” —the stroke/throw of the machine wasn’t long enough —and wasn’t suited for getting ink into the skin.

Modern day rotary tattoo machines also greatly depend on cam mechanics, but they’re fitted with a round shaped “eccentric cam” with an off-centered pin rather than an armed cam. Many of today’s rotary machines are constructed to fit a variety of different sized eccentric cams, which adjust the machine’s throw, so it can be used for either outlining or shading or coloring. i.e. larger cams lengthen the throw, smaller ones shorten it. (Note: The terms eccentric and cam are often used interchangeably).

Did O’Reilly know about the function of the cam? Unfortunately, since O’Reilly’s foremost invention claims were the custom tube assembly and the addition of an ink reservoir, he wasn’t required to outline the cam or cam mechanism on his patent application. Take note, however, that the cam on O’Reilly’s accompanying diagram is conspicuously diamond-shaped instead of three-pointed as on Edison’s rotary. It also appears to be of larger proportion. If O’Reilly’s diagram is true-to-life, it suggests he was aware to some degree that changing the cam would affect how the machine operated. Why, then, did he go to the greater extent of devising a complicated tube assembly?

Maybe O’Reilly wasn’t able to implement a cam that completely solved the adaptability issues of the Edison pen. It’s just as possible the modified tube assembly was intended to make the machine even more functional above and beyond a fitting cam. Whatever the case, it seems that at some point someone (maybe even O’Reilly) did discover a cam (or multiple cams) that worked sufficiently enough for tattooing.

Quite pertinently, a year and a half after the 1891 patent was in place —in July of 1893 —the Boston Herald published an article about Captain Fred McKay of Boston, and distinctly described his tattoo machine as an “Edison electric pen” with a “larger eccentric” to “give the needle more play;” he used this type of machine for both outlining (with one needle) and shading (with seven needles).

Since the article doesn’t illustrate McKay’s machine, we can’t be 100% sure it didn’t also include O’Reilly’s specialized tube assembly. However, it’s pertinent that the Boston Herald reporter singled out the altered cam, a small tucked away feature, over a large outward modification such as a re-configured tube assembly. Moreover, all evidence indicates that altering the cam was a feasible adaptation; one that also accounts for the existence of straight-handled Edison pen-tattoo machines. (See postscripts 1 & 2)

Other Types of Machines:

Did early tattooers use a variety of different size cams to adjust the throw on the Edison pen? Were additional modifications required? Also, would the cam solution have been more or less effective than O’Reilly’s tube assembly system? And which came first? Who can say. One thing is certain progression in technology requires ongoing trials —constant tinkering, testing, and sharing of knowledge. Patents are just one facet of the process.

O’Reilly’s patent innovations were important and surely led to additional experimentation and discoveries. At the same time, there must have been numerous un-patented inventions. It stands to reason that there were multiple adaptations of the Edison pen (In a March 4, 1898 Jackson Patriot news article, an ex-sailor named Clarence Smith claimed to have adapted the Edison pen for tattooing around 1890 by somehow “shortening the stroke” and “altering the needle”). Early tattooers no doubt constructed a miscellany of machines with diverse modifications, influenced by perforating devices, dental drills, engravers, sewing machines, telegraphs, telephones, and many other related devices; some we’ve never seen or read about and some that worked better than others.

O’Reilly’s extensive media coverage offers some clues about the range of machines. A correspondence report in the October 21, 1894 edition of the Los Angeles Times described one of his machines as such (See Postscript 3):

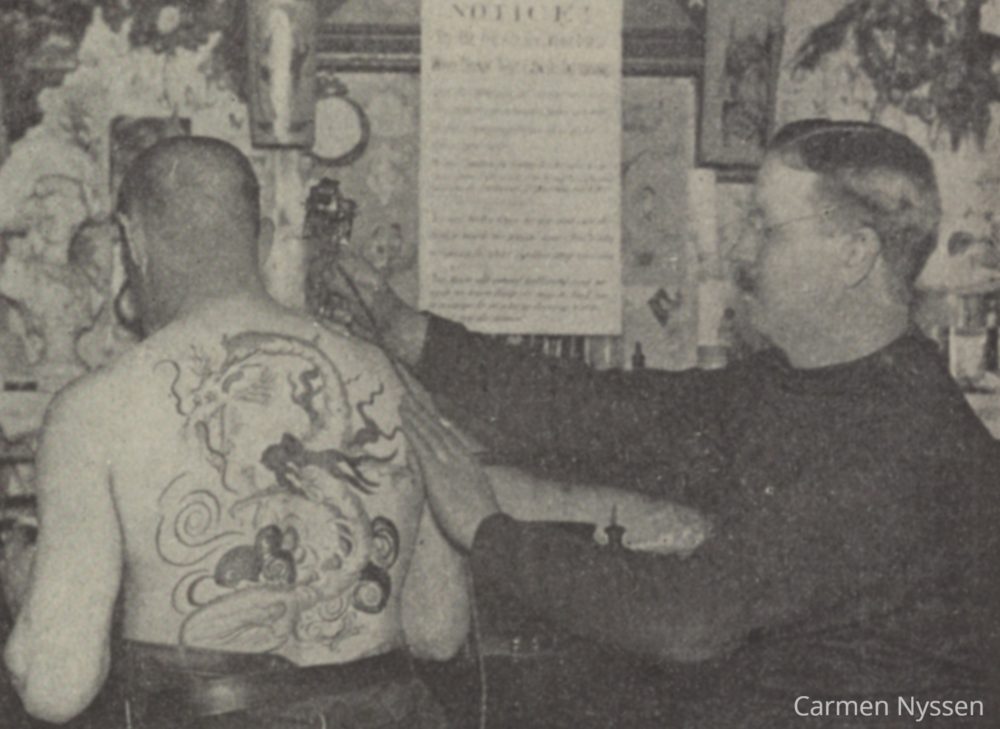

While care should be taken with media reports, the consistent use of the word “hammer” in the article invokes something other than an Edison pen; a dental plugger aka dental hammer is what comes to mind. (A trip hammer’s pivoting hammer arm shares an uncanny resemblance with the like part on a dental plugger). That O’Reilly might have been tattooing with a dental plugger even after his patent was in place is not so farfetched. The device he’s holding in the image seen here in this 1901 article looks suspiciously like a dental plugger.

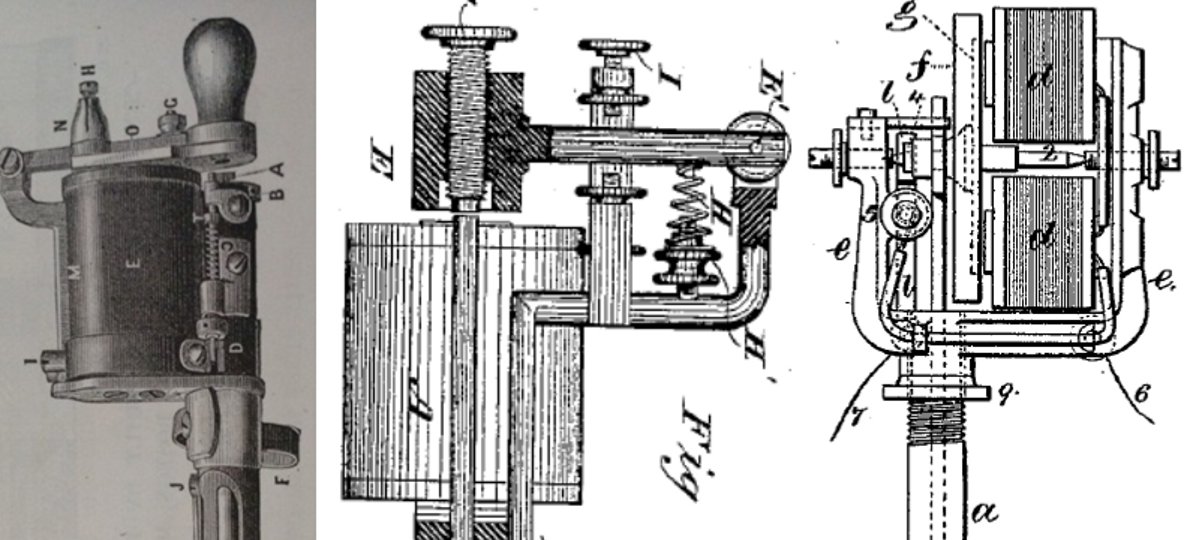

Left: Bonwill’s improved dental plugger, Bonwill’s 1878 patent, Edison’s 1876 rotary stencil pen patent.

__

Yet another report in an 1897 Nebraska Journal article, described O’Reilly outlining tattoos with a “stylus with a small battery on the end,” and putting in color with a similar, but smaller, machine using more needles. The article does not specify the types of machines, though the word “stylus” implies a straight-handled device. Also, the fact that they differed in size indicates they probably weren’t Edison stencil pens, which as far as we know came in one standard size.

The same article goes on to describe O’Reilly’s shading machine, which operated by clockwork instead of electricity. It had fifty needles and was “actuated by a heavy [clockwork] spring.” This machine may be the one depicted in a September 11, 1898 Chicago Tribune illustration of O’Reilly tattooing dogs. It looks similar to other perforator pens of the era, a good example being the pattern making device patented by British sewing machine manufacturers Wilson, Hansen, and Treinan (UK 5009)December 7, 1878. This device had a wind up mechanism akin to a clock and is said to have been modified for tattooing.

See the Buzzworthy Tattoo History biographical sketch, Samuel F. O’Reilly, for history about his early life in Waterbury, CT working in local clock factories.

Sam O Reilly Tattooing Dogs, Chicago Tribune, Sep 11, 1898. Print.

Another unique machine appears in an October 1899 Ev’ry Month Magazine article about O’Reilly, England’s Sutherland McDonald, and Japan’s Hori Chiyo. The author of the article, however, didn’t offer specifics on this device.

Elmer Ellsworth Getchell:

An innovator of this era, who never obtained a patent for his invention, was ‘Electric’ Elmer Getchell (1863-1940), a longstanding tattoo artist from Boston. Getchell’s descendants say he was “scholarly” and “a jack of all trades,” skilled as a steamboat captain, horseshoer, chemist, and water color artist. Family lore also says he was the inventor of the modern day electric tattoo machine.

During the Spanish American war Getchell partnered with O’Reilly in his New York Bowery shop at 5 Chatham Square. Ultimately, they had a falling out. According to documents of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, in April of 1899, O’Reilly filed charges against Getchell, claiming that he had infringed on his patent by selling machines made according to the patent “within the district of Massachusetts and elsewhere,” and that he was “threatening to make the aforesaid tattooing machines in large quantities, and to supply the market therewith and to sell the same…” Getchell then hired a lawyer and moved to a new shop down the street at 11 Chatham Square.

In his rebuttal testimony, Getchell clarified that his tattoo machine was not made “employing or containing any part of the said alleged invention [patent].” He further proclaimed that O’Reilly didn’t even use the patent machine, because it was “impractical, inoperative, and wholly useless.” Most significantly, he maintained that the foundation of O’Reilly’s machines was, in reality, invented by Thomas Edison.

The last part of Getchell’s argument held particular weight. While he had likely borrowed ideas from other devices to create his machine, even O’Reilly’s (i.e. an ink reservoir), he only had to demonstrate the novelty of his invention, just as O’Reilly had done with his patent. As an aside, Getchell called upon patent expert Octavius Knight to testify in the case. Court documents do not specify whether Knight ever took the stand, but about the time he was expected to appear, the case was dropped.

Getchell’s Tattoo Machine:

So what exactly was Getchell’s invention? Court papers refer to two of Getchell’s machines, Exhibit A, the machine he was currently using, and Exhibit C, a machine he’d supposedly invented in prior years. Unfortunately, neither is illustrated in any detail. Tattoo artist Lew Alberts (1880-1954) described Getchell’s invention as a “vibrator” in a 1926 interview with the Winston-Salem Journal, which he differentiated from O’Reilly’s “electric needle.” The term “vibrator” infers that Getchell’s machine operated by way of a vibrating electromagnetic motor. (Edison referred to his electromagnetic stencil pen as a “vibrator.”)

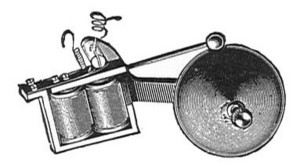

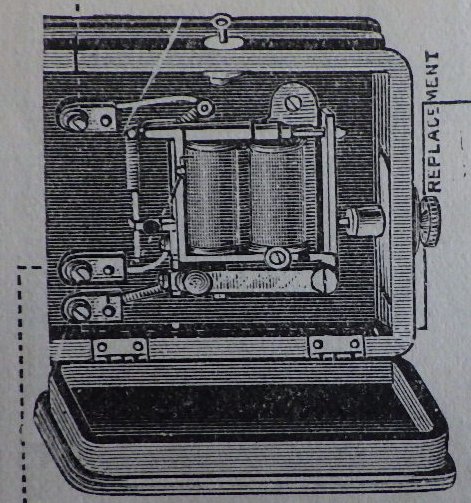

Alberts’ description isn’t specific and could have referred to a number of electromagnetic devices. But a grainy picture of Getchell’s machine in a 1902 New York Tribune article looks very much like a current day tattoo machine, complete with an L-shaped frame and dual front-to-back (in line with the frame) electromagnetic coils.

__

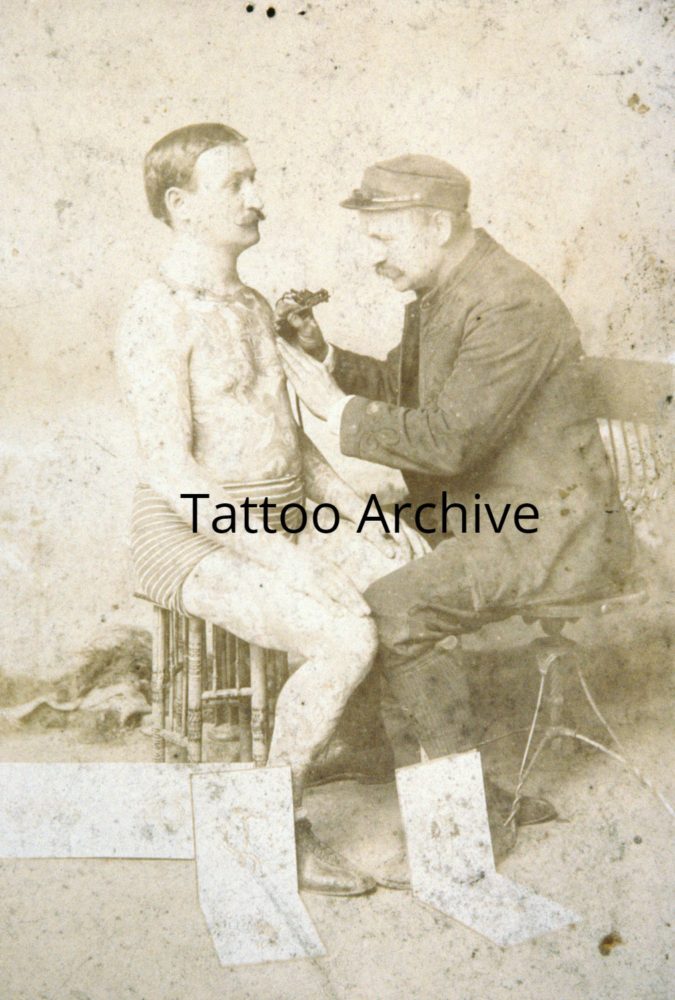

A clearer duplicate of this image seen below —which once hung in the tattoo shop of famous Norfolk, Virginia tattoo artist “Cap” Coleman and is now housed in the Tattoo Archive (Paul Rogers Collection)—settles any uncertainty over the matter. Getchell’s machine was absolutely the same as a modern day build.

Elmer Getchell tattooing Otto Schmidt c. 1902. Collection of Tattoo Archive

__

Evidently, Getchell had been using this type of machine for some time. The 1902 New York Tribune article reported that he had invented it “a number of years” prior, inferably around the time O’Reilly brought charges against him. Perhaps even earlier. As noted, O’Reilly claimed Getchell had made and sold his machines “within the district of Massachusetts.” It’s quite possible that Getchell had invented the machine in question before he permanently left his hometown of Boston, Massachusetts in 1897.

It’s well established that modern tattoo machines are based on vibrating bell mechanisms —operated by two electromagnetic coils, which actuate the vibrating motion of an armature and hence the reciprocating motion of the needle. More specifically, the type with the armature lined up with the coils. Vibrating bell mechanisms were quite powerful, ingeniously streamlined constructions used in various types of alarms, annunciators, indicators, and doorbells from the mid-1800s on. Whether it was actually Getchell or someone else, who once again, made the intuitive leap of transforming a stand alone electromagnetic mechanism into a handheld device, the bell tattoo machine had irrefutably taken hold by the turn of the century. A number of period photos have turned up depicting quite modern looking machines.

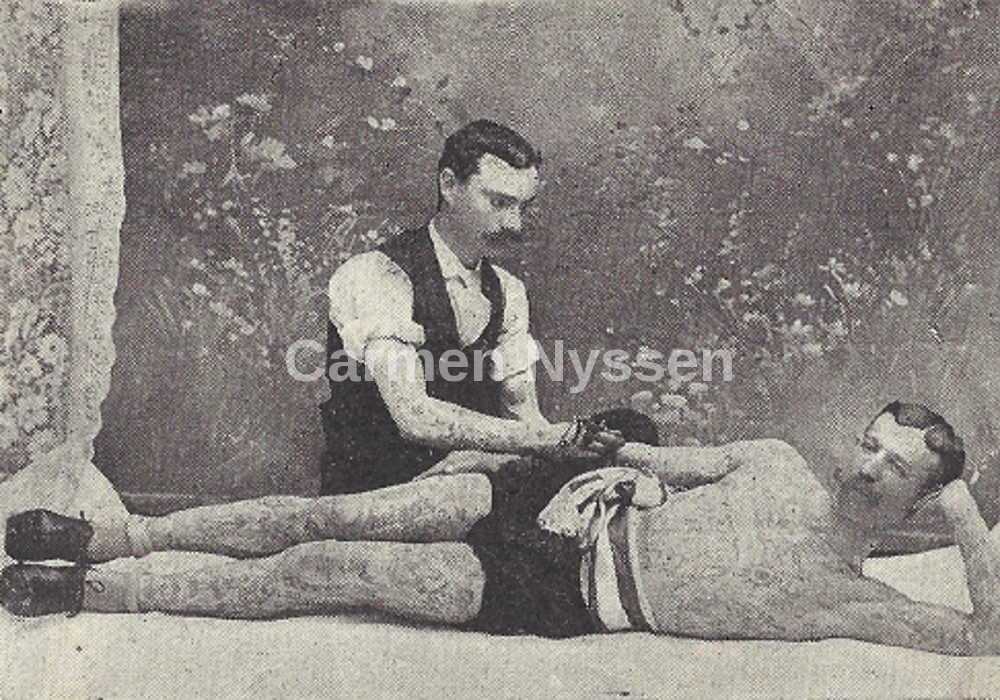

Boston tattooer Otto Mason. New England Home Magazine. Nov 18, 1900. Collection of Carmen Nyssen

New York World, August 1, 1897, pg. 37: An article about lesser known New York City tattooer Frank Childs describing his tattooing device: “The electric [tattoo] machine works on the same principle as an electric bell —that is, the alternate opening and closing of a circuit gives three needles a rapid motion like that of a jig saw. One of those needles is longer than the others, and it opens the flesh. The other needles hold the ink and distribute it in the furrow made by the other pointed bit of steel.”

Bell Tattoo Machines:

We may never know the precise date the first bell tattoo machine was made. But it’s possible their seemingly sudden popularity is connected with the emergence of late 1800s mail order catalogs responsible for bringing affordable technology to the door of the average citizen. Sears Roebuck and several other retailers set the trend when they began offering a wide range of merchandise via postal mail; the assortment of electric bells (i.e. alarms, annunciators, and doorbells), batteries, wiring, et cetera would have provided a multiplicity of inspiration for tattoo artists.

Interestingly, the catalogs marketed certain types of bells (particularly doorbells) as “outfits.” Due to lack of electrical wiring in most homes and buildings, the kits consisted of a battery, wiring, and either a nickel or wood box encasing. There’s something to be said for the fact that tattoo machines were also sold as “outfits,” complete with batteries and wiring. (In England, on March 24, 1900, Alfred South of England actually received a patent for a tattoo machine based on a doorbell mechanism (UK 13,359). It also included the doorbell encasing).

However tinkering tattoo artists were introduced to bells, the discovery made way for a whole new world of innovation. With so much variety in bells and the versatility of their movable parts, tattoo artists could experiment with countless inventive combinations, all set to operate on an exceptionally reliable mechanism.

Bell mechanisms were typically mounted on a wood or metal base, so they could be hung on a wall. Not all, but some, were also fitted in a frame that was intended to keep working parts properly aligned despite the constant jarring of the bell. With minor modification a bell mechanism, especially those with a frame, could be removed from the wood or metal base and converted into a tattoo machine; i.e. adding a needle bar, tube, and a tube holder (vice) of some type.

The general consensus is that the earliest bell tattoo machines were built up/modified bell mechanisms, with additional parts, such as the tube and/or vice, welded or screwed on. Later, as tattoo machines evolved, frames were cast from customized intact molds, then assembled by adding the adjustable parts; i.e. the armature, coils, needle bar, armature springs, binding posts, contacts, etc.

The Single Upright Machine:

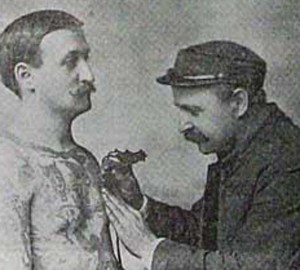

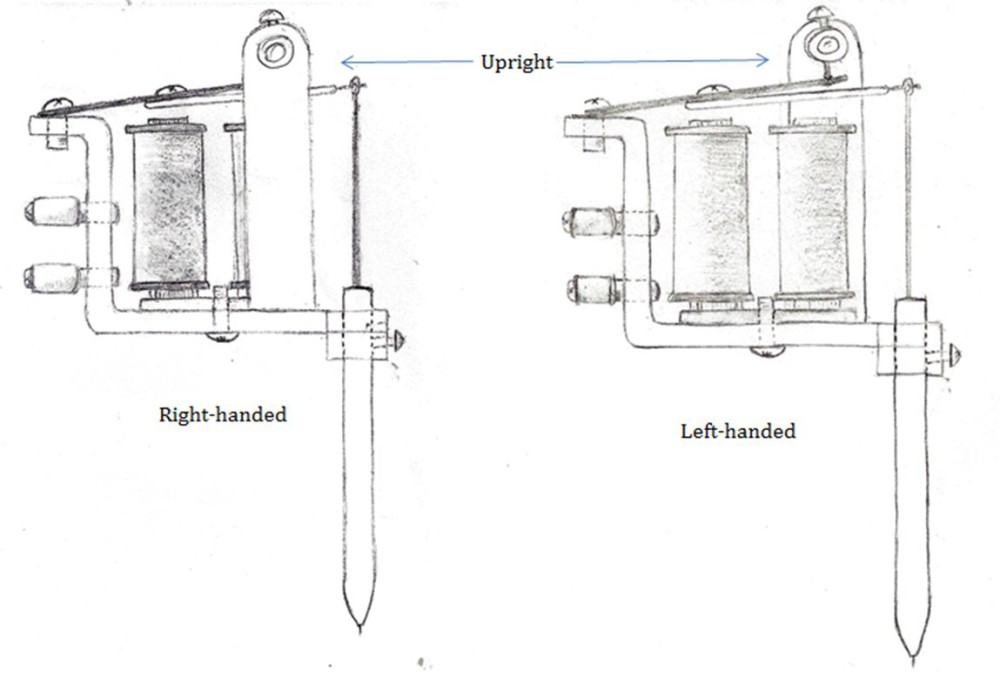

One particular bell set up provided the framework of a tattoo machine style known today as a “classic single-upright” –a machine with an L-shaped frame, an upright bar on one side and a short “shelf” extending from the back side.

The single upright machine (with some variation) has been a decades long standard. Although its date of origin has been debated, this type of frame can be seen in bells as early as the late 1880s.

- Vibrating bell mechanism. Allsop, F.C. Electric Bell Construction. New York & London: Ballantine Press, 1889. pg. 32. Print.

- Amateur Work Magazine Vol.Draper Publishing Company, 1902

- Rankin Kennedy, Electrical Installations, Vol V, 1903

—

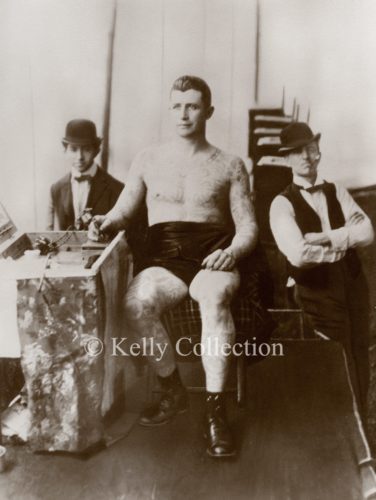

Getchell’s machine appears to be based on a comparable design, as does the machine depicted in the circa 1897-1900 photograph of tattoo artist George Kelly (aka Karlavagn) seen below.

George Kelly aka Karlavagn, c. 1897-1900. (Karlavagn had retired from tattooing by the end of 1900). Photo courtesy of Kelly Collection.

—

A closer look at the Kelly and Getchell machines reveals something else.

On Kelly’s machine the upright bar is on the “left side” of the machine…..

……while on Getchell’s machine the upright is located on the “right side.”

Machines with left-side uprights are referred to as left-handed machines. Machines with right-side uprights are referred to as right-handed machines. (It has nothing to do with whether the tattoo artist is left-handed or right-handed).

It’s generally believed that left-handed machines came first, because the frame is akin to typical bell frames of the era. Right-handed machines, which eventually won out over left-handed machines, are thought to have been introduced around or after the 1910s. However, as evidenced by the Getchell photo, right-handed tattoo machines were made at a significantly early date.

That’s not all. The reason right-handed tattoo machines are thought to have come later is because they are viewed as spin-offs of left-handed machines, the assumption being that the right side upright was a never-before-seen innovation implemented by an experimenting tattoo artist. (i.e. a frame casting mold was “invented” that positioned the upright on the right side rather than the left side). As it turns out, bell frames with right side uprights existed alongside their left-sided counterparts. Though they seem to have been rarer, they very well could have provided the inspiration for right-handed tattoo machines.

Allsop, Frederick Charles. Practical Electric Bell Fitting. New York & London: Ballantine Press, 1889. Pg. 44. Print

Bell-Influenced Innovations:

There are far too many bell-influenced adaptations to outline in this article. But one prominent example is the back return spring assembly modification that has often been implemented in tattoo machines over the years. On bells —with or without a frame —this set up consists of a lengthened armature, or an extra steel pivoting piece, extended past the top back part of the armature. The armature or pivoting piece is steadied by two screws at a pivot point, then a return spring is attached at the backmost end and anchored to bolt below. According to one catalog description, these bells produced “a powerful blow” perfect for an alarm or railroad signal.

Iron Bell Frame, Stanley & Patterson Company Catalog c. 1895. Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York

The set up on tattoo machines is similar, except a rubberband is sometimes used instead of a return spring. Basically, a rubberband or return spring is attached to the top, backmost part of a lengthened armature and then secured to a modified, lengthened post at the bottom end of the frame. The back return spring essentially regulates tension and proper functioning, the same as the back armature spring on modern tattoo machines.

Relay Burglar Alarm. Hasluck, David. Electric Bells. Philadelphia: David McKay, 1903. Print

The pivoting armature-return spring set up might have been first implemented at an early date. Notably, bells with the corresponding structure were sold by companies like Vallee Bros. and Stanley & Patterson and Company in the mid-to-late 1890s.

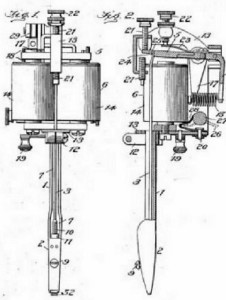

Charlie Wagner implemented a variation on this idea in his 1904 patent machine (US Patent 768,413). His version consisted of an extended pivoting piece connected to the armature that bent downward at a 90 degree angle off the back of the machine frame; the return spring was connected horizontally, between the bent down arm and the machine, rather than vertically.

The pivoting armature-return spring set up actually goes back much further. It was an important component of some of the early 1800s telegraph relay systems (though in telegraphs, the coils, armature, and return spring were positioned differently). To emphasize how much overlap there is in invention, both of W.G.A. Bonwill’s twin-coiled dental plugger patents (and the improved, manufactured model) employed variants of this set up. It shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, Bonwill was inspired by the telegraph.

Supply Businesses:

The advent of the bell tattoo machine —the machine of future generations —stands as a major turning point in tattoo history. Did it kick-start the manufacturing of tattoo machines and pave the way for supply businesses? There certainly seems to be a correlation. The impression is tattoo machines were only being “made” and sold on a minute scale in the late 1800s, possibly because there wasn’t yet a standard machine (and perhaps to a degree because of infringement issues). From what is known thus far, the earliest machines seem to have been fashioned from a variety of pre-manufactured, modified devices (i.e. dental pluggers, stencil pens, and the like). The introduction of the highly operational bell tattoo machine changed this dynamic substantially.

As noted, in addition to greater power and a streamlined design, bell mechanisms possessed greater modification potential; mainly because they were not intact handheld machines and the parts were more readily adjustable. Freedom from pre-existing construct, combined with insight from years of trials, allowed tattoo artists the vantage of assembling, and further developing, a machine outfitted expressly for tattooing. In other words, machines could be constructed in a more trade-specific manner and manufactured and marketed as such (assumedly free from infringement).

An explosion of tattoo supply ads just after the turn of the century, suggests a significant shift of some type had taken place. Between 1901 and 1905, a handful of tattoo artists, including Sam O’Reilly, Charlie Wagner, Lew Alberts, Frank Howard, and Edwin E. Brown, began steadily advertising electric tattoo machines and other supplies for sale in nationwide trade magazines, such as, The National Police Gazette and Billboard Magazine. The stalemate outcome of the O’Reilly-Getchell case might have opened the door to opportunity. However, since the marketability of products generally depends on standardization, the emergence of supply businesses most logically rests with the trade-worthy bell machine (standardization relative to the era, mind you). As demand and competition grew, machine quality would have continually increased.

Charles Wagner:

Tattooing Device. Charles Wagner, assignee. Patent 768413. 23 Aug. 1904. Print

Though early tattoo machines evolved in great strides in just a short amount of time, the second tattoo machine patent (US Patent 768,413) didn’t come along until thirteen years after the first. It was issued on August 23, 1904 to New York Bowery tattoo artist Charles Wagner (1875-1953), an alleged student of Samuel O’Reilly. He appears in records starting in 1899; first at 294 Houston, then by 1901, at 294 Stanton, where he sold a “Complete electric tattooing outfit, including machines, batteries, designs, stencils, and eight different colors;” later at 223 ½ Bowery, his shop locale for a good number of years. (When O’Reilly died on April 29, 1909, Wagner took his spot at 11 Chatham Square)

It’s been said that O’Reilly helped Wagner develop his patent machine. However, Lew Alberts (real name Albert Morton Kurzman) is one of the witnesses who signed his patent. As a teen, Alberts attended the Hebrew Technical Institute in New York, where he learned a variety of skills, including shop and metal working. School records note that he broke into the tattoo trade in 1904, the same year Wagner’s patent was issued. My research on Alberts is featured in the book: Lew the Jew Alberts, Hardy Marks

Wagner’s patent claimed numerous innovations, including an on/off switch, stroke adjustment via contact screws, a tube vice, a tube with an ink hollow, and interchangeable needle bars.

The needle bars had an eye hole at the top end, so they could be detached from or secured to a “nipple” on the front and side of the armature. The needle bars were comprised of either single or multiple needles, which were affixed in a correspondingly fitted tube, also detachable and held in place by a vice. According to the patent text, the latter modifications permitted the same machine to be used as either a liner or a shader. This machine, or a derivative, might be the one Wagner advertised in Billboard Magazine in 1905:

“Electric Tattooing Machine For Sale-Changeable Machine to do both outlining and filling in colors with switch board $10. Colors: yellow, green, light blue, red, brown, black, and range, 50cents per cup. This is part of my price list. Prof. Wagner 223 ½ Bowery, New York City.”

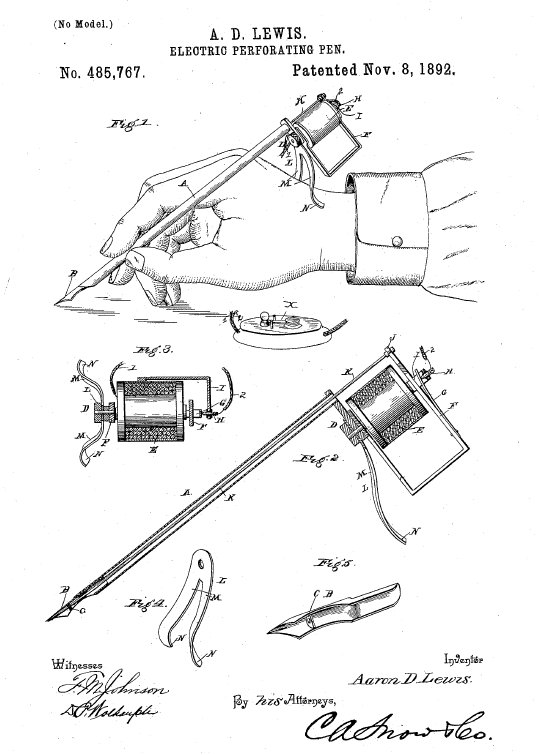

Electric Perforating Pen. A.D. Lewis, assignee. Patent 485,767. 8 Nov. 1892. Print.

Wagner’s patent incorporated a conglomerate of borrowed ideas. Because of this he encountered the same problems as O’Reilly upon submitting his application. Wagner’s claims were rejected at first:

(1) Based on O’Reilly’s earlier 1891 patent (US Patent 464, 801) with reference to the needle rod connection and the armature. Rejection notes state it would not be invention to add this part to a “motor and controlling device” similar to Edison’s 1877 stencil pen (US patent 196,747).

(2) Because the on/off switch was analogous to that of Aaron D. Lewis’ 1892 stencil pen (US Patent 485, 767) and it would not be invention to add it to the O’Reilly patent frame.

Just like O’Reilly, Wagner had to revise his patent claims. In the end, of course, he proved the novelty of his invention and his patent was issued.

Which parts of Wagner’s patent modifications were new to tattoo machines? We just don’t know. But it’s clear now he wasn’t the pioneer of electromagnetically operated tattoo machines, as is so often reported in tattoo history write-ups. These types of machines —in the form of both dental plugger and bell tattoo machines —were in use well beforehand.

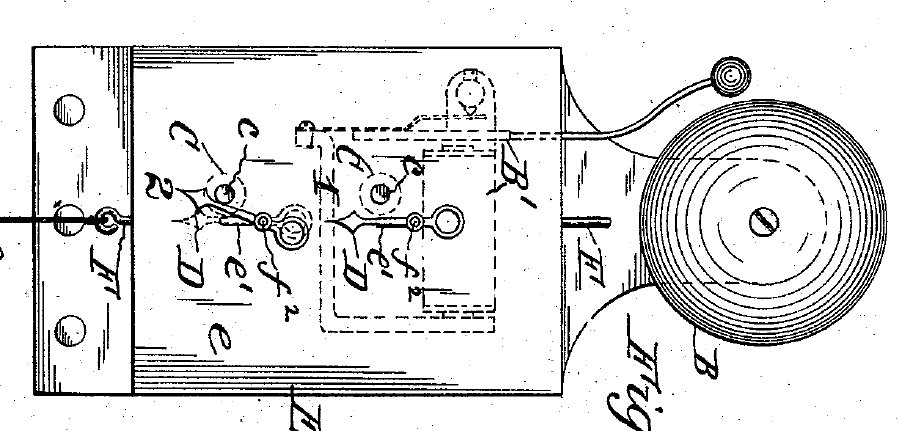

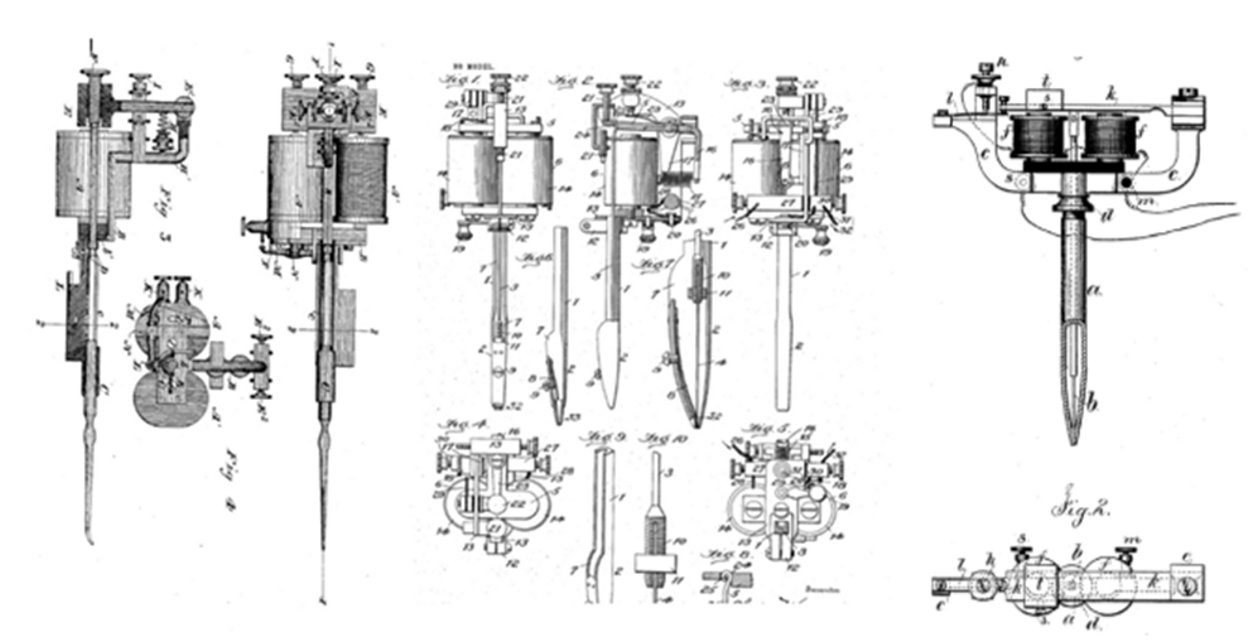

Wagner’s device was actually a bit of a deviation from the popular bell tattoo machines. Rather than front-to-back coils (in line with the frame), the coils on Wagner’s machine were set side-by-side (transverse to the frame) ……more like a dental plugger. In fact, although Edison’s 1877 stencil pen (US patent 196,747) is usually cited as the inspiration for Wagner’s machine, as seen in the below images, it was strikingly more similar to Bonwill’s 1878 dental plugger patent (US Patent 209,006).

Bonwill patent left, Wagner patent center, Edison patent right.

__

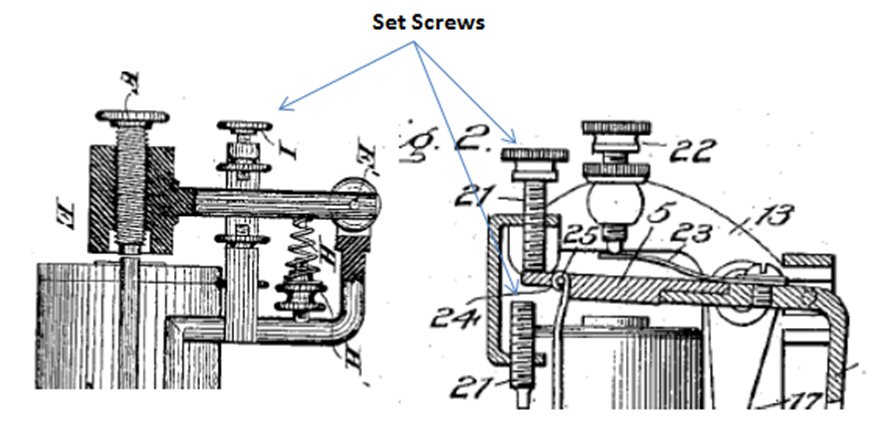

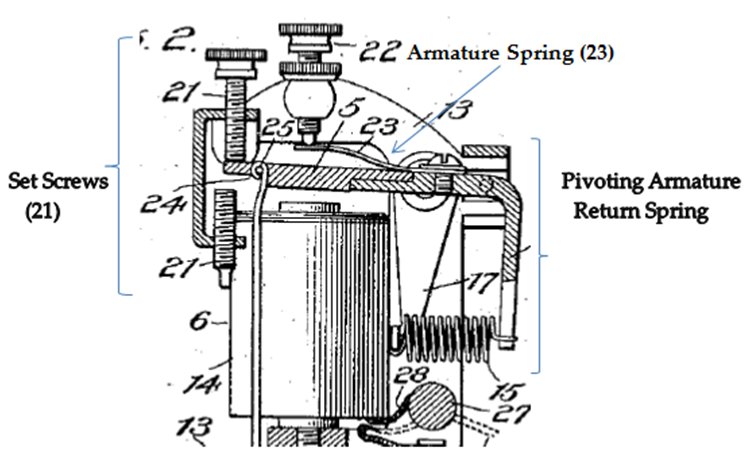

The two patents shared likenesses beyond the framework. They both included stroke adjustment by way of loosening or tightening set screws that acted on the armature; much like in telegraphs (See here). On Bonwill’s device, one adjustable set screw in conjunction with another stable set screw underneath, worked on an arm extended off the armature. The set screws on Wagner’s device were positioned the same in relation to one another, but they were both adjustable and worked on the front of the armature to where Wagner had arranged the needle assembly. Due to the set screw’s front armature placement, the “nipple” (the needle bar attachment) was forced to a side position on the armature, instead of a front position as it would have been on a bell machine.

Bonwill’s patent left, Wagner’s patent right.

__

As previously mentioned, both machines operated by way of a pivoting armature-return spring assembly, each set up a bit differently. On Bonwill’s device, the armature (the hammer piece) and armature arm operated with a wheeled pivot and a vertical return spring supported by a frame below. This arrangement was devised to facilitate the hammering action of the dental plugger. Unlike Bonwill’s device, Wagner’s had a flat armature (#5 on the illustration) and also an armature spring (#23) and armature spring contact (#22); a set up meant to produce the desired reciprocating action for tattooing. Wagner’s modification of the pivoting armature-return spring combo, with the bent down extended armature piece and horizontal return spring, was likely adapted to accommodate these additions.

Tattooing Device. Charles Wagner, assignee. Patent 768413. 23 Aug. 1904. Print

The implementation of the flat armature, armature spring, and armature spring contact on Wagner’s machine explains why the patent office compared his “electromotor and controlling device” with Edison’s 1877 stencil pen instead of with a dental plugger or like device. Edison’s invention was the first patented, handheld device to employ this set up.

In the realm of patents, where an official patent registration dictates novelty, this assessment was accurate. In reality, Wagner’s implementation of the said parts was undoubtedly directly inspired by the not yet patented bell tattoo machines that tattooers had been working with for a number of years. The set up in bells is a closer match. Even in patent text Wagner specifies that the “electrical connections” on his machine (coils, armature, contact, and armature spring) operated similarly to a bell mechanism.

Charlie Wagner tattooing with a modified dental mallet. Image courtesy of Jon Reiter, Solid State Tattoos & Publishing.

Given the seeming popularity of bell tattoo machines at the turn of the century, we can only guess at why Wagner patented a device in 1904 with so many similarities to Bonwill’s 1870s dental plugger. Bonwill didn’t mass-produce his actual patent model. Although Bonwill had implemented some versions for use in dentistry beforehand, by the time his dental plugger was commercially manufactured and marketed it had undergone ample improvement (for dentistry purposes) and many of the features seen in Wagner’s patent had been streamlined out.

Perhaps one of Bonwill’s earlier prototype models or another device based on it passed through the hands of tattooers. The fact that tattoo artists had tattooed with dental pluggers of any kind could have inspired Wagner in some way. There’s slight evidence O’Reilly was still using a dental plugger at the turn of the century; maybe this had some bearing on his idea.

Of the many possibilities, it could be that the resemblance of the two devices is merely coincidental. As we know, throughout history, inventors have often converged on like ideas. Perhaps, as with Edison and Bonwill, Wagner’s ‘Eureka moment’ came to him after seeing a telegraph, or related device, in operation.

Whatever circumstances led to Wagner’s reworked combination dental plugger like-bell tattoo machine invention, it was certainly a creative contrivance. The overall framework of his patent wasn’t exactly an improvement over bell tattoo machines, otherwise tattoo machines would look very different today. Yet it was still an important contribution; some of Wagner’s innovations must have been new to tattoo machines and many became standard features.

As proof of Charlie Wagner’s innovative prowess: “Around 1920, at his 208 Bowery factory, Wagner innovated a device intended to better facilitate the tattooing process. On March 25, 1920, he filed a patent, the first ever, for a tattoo-trade-specific rheostat.” See my article Charlie Wagner’s ‘Chatham Electric Tattooing’ Enterprise (link at end of article).

In sum, what Wagner’s patent represents —as does all invention —is the continual experimentation necessary to refine technology. Like many others for years to come, Wagner forged ahead with his trials. He eventually became one of the top tattoo machine manufacturers in the country. Incidentally, Wagner was a huge influence on Percy Waters, who later operated his own very successful tattoo machine manufacturing company, and who obtained the third tattoo machine patent on January 30, 1929, 24 years after Wagner’s was issued. Waters’ patent machine wasn’t “new” per se. It was a single-upright machine, fitted with features which had already been discovered by one ingenious tattooer or another and employed in tattoo machines for years. But his patent did introduce a number of novel innovations.

Nature of Invention:

All the innovators mentioned, herein, and nameless others —whether they held patents or not —did their part in developing what we now think of as an electric tattoo machine. It would be very difficult to pinpoint one person as the “true inventor” at any point in time, or any one innovation as the most supreme. Invention is a complex matter. It’s not a singular occurrence. It’s pliable and flowing. It’s a convergence of ideas; a mixture of those already in existence and those newly formed that come together depending on what a device is being used for. And, not to mention, after much experimentation.

Thomas Edison and his team of inventors borrowed a plethora of ideas for their inventions; experimentation resulted in practical devices and others not so practical. For example, in developing the stencil pen, they looked to existing telegraph and rotary technology to create a variety of rotary operated, electromagnetically operated, and hybrid devices. The resulting machines were presented all together in an 1875 British patent (UK 3762). After further trial, the device we know of as the “Edison pen,” the model for O’Reilly’s tattoo machine, proved preferable for stencil making. That’s why it was the first one patented in the U.S. (US Patent 180,857). In patent text, Edison acknowledged that a vibrating armature instead of a rotary motor could be used to operate his stencil pen, but pledged his resolve for the latter: “…I [Thomas Edison] have invented numerous devices for which I contemplate applying for Letters Patent, hereafter. I have only shown herein the device which I prefer to use…” As we’re aware, Edison later patented a vibrating armature stencil pen in the U.S., probably to stake his invention claim, but he didn’t manufacture it. If he had, early tattoo machines might have evolved along a bit different path.

In the tradition of all the great innovators, tattoo artists instinctively embraced the concept of borrowing ideas and repurposing them. In most cases, neither the machines they experimented with, nor the tweaks required to make them tattoo-ready were entirely new to the invention world. That’s the point. Building off existing ideas doesn’t lessen the value or novelty of an innovation. Fusion of ideas is an inherent premise of invention. When you put it in perspective, the early innovators of tattoo machines were extraordinary pioneers. They did not have the benefit of substantiated invention in their field. Electricity itself was only just beginning to pervade daily living, and at the time, laymen weren’t typically educated in that technology. What the early tattoo artists achieved as a whole was remarkable. Relatively speaking, it was no less revolutionary than the breakthroughs of, say, Thomas Edison or William G. Bonwill. Together the early tinkerers transformed the trade of tattooing.

Post Scripts:

1) It would be interesting to know whether Edison pens were actually manufactured according to patent specification with a three-pointed cam, or whether a different size/shaped cam proved better-fitted once the pens were put into practical use. Also, a collaborative, comparative hands-on study of surviving Edison pens would likely offer further insight into how they could have been modified for tattooing, and possibly whether any of those surviving were, in fact, used for tattooing. The same applies to all relevant devices.

2) O’Reilly’s patent illustration depicts a flywheel that is proportionally larger and thicker than the flywheel in the illustration of Edison’s stencil pen; it also has spokes. A flywheel’s job is to regulate movement by storing energy and steadily releasing it. Larger flywheels and/or flywheels with spokes release more energy. It’s not clear how effective a modification like this would have been within the constraints of such a small machine. Too large or heavy a flywheel tends to cause friction, and due to its increased power, can burn out a motor if it’s not in proportion to the other working parts of the machine. Notably, some photos depict straight-handled Edison pen-tattoo machines without the flywheel modification. The Edison pen-tattoo machine housed in the Tattoo Archive does include this modification. (Depicted in Skin & Bones Tattoo Exhibit catalog).

3) Several blogs mention a Sunday, Los Angeles Times article dated October 21, 1884 that describes Samuel O’Reilly tattooing with “a number of fine sewing needles …fixed firmly in a block of wood…attached to a sort of trip hammer, which runs by an electric battery.” The date given for this article is off by 10 years. The article was actually published in the Sunday, Los Angeles Times, October 21, 1894.

4) Early Tinkerers of Electric Tattooing by Carmen Forquer Nyssen has been resourced in numerous publications, exhibits, academic dissertations, and related projects.

Publication:

See Carmen Forquer Nyssen’s published feature article Ever-Evolving Tattoo Machines in the 2018 book TTT: Tattoo.

Includes timeline and original, groundbreaking research on the first electrically tattooed attractions and electric tattoo machines.

Buzzworthy Tattoo History Feature Articles:

With indepth research on the expansion of the tattoo trade in conjunction with sailor culture, dime museums, circuses, and electrical tattooing:

Saloon Tattoo Shops of New York City’s 4th Ward

Barnum & Bunnell’s Tattooed Humbugs: Manifesting a Tattoo Trade

A Tattooed Affair: Earliest Tattooed Attractions

Birth of the Tattoo Trade: New York Bowery

Tattooed by O’Reilly: The First Electrically Tattooed Attractions

John O’Reilly: Tattooed Irishman

New York Tattoo Shops: 5 & 11 Chatham Square

Samuel F. O’Reilly Vs. Elmer Getchell

Charlie Wagner’s ‘Chatham Electric Tattooing’ Enterprise

Charlie Wagner: King of Bowery Tattooers