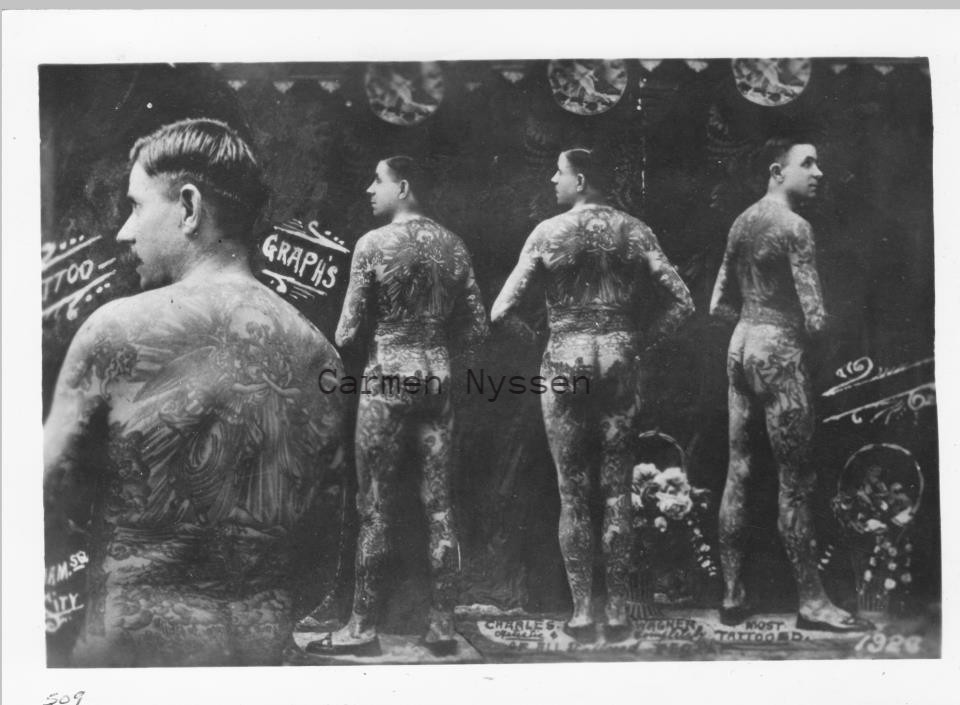

Tattoo Artist Charlie Wagner. Tattoo memorabilia collection of Carmen Nyssen.

Charlie Wagner

Original research by Carmen Nyssen

Born: January 20, 1875 Prešov, Slovakia

Died: Before July 1953, New York (End note 1)

There’s a reason Charlie Wagner (born Wiegner) is the tattoo artist that comes to mind when the topic of New York, or Bowery, tattoo history is brought up. For over fifty years—from his humble start practicing his craft in the Lower East Side slum, to succeeding the throne of the famed Samuel F. O’Reilly in Chatham Square, and even his declining years on the Depression-worn Bowery—he persevered in the tattoo trade, loyal to his New York City roots.

Like so many New York City residents, however, Charlie Wagner wasn’t a United States native. He was born on January 20, 1875 to Karl Eduard Joseph Wiegner (aka Edward, 1850-1928) and Matilda Gabriela Hvistko (1850-1890) in Prešov—then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and now East Slovakia. Though it has been said that Wagner was Jewish, his family belonged to the Lutheran Evangelical Church (End note 2).

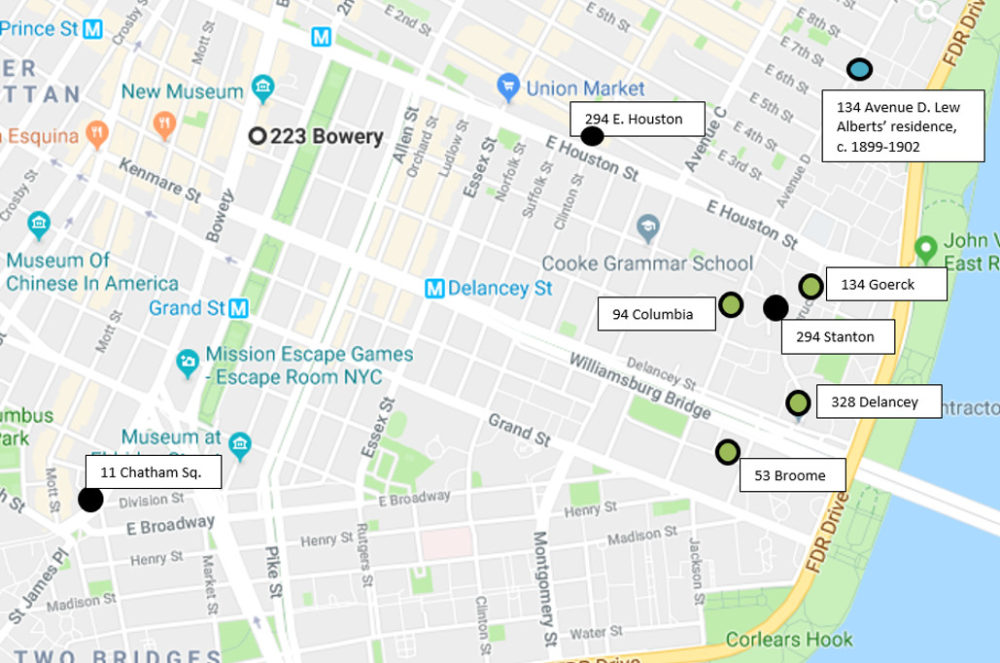

According to census notes, the Wiegners left for America in 1880, when Charlie was five-years-old. Upon their arrival in New York City, his father, Edward, took up work as a cooper and settled the family in the immigrant-filled Lower East Side (LES), where they variously resided at 94 Columbia, 328 Delancey, 134 Goerck, and 53 Broome. It was here in the squalid living conditions of overcrowded tenements, set along streets and back alleyways rife with all imaginable vices, that Wagner learned his way in the world and hurdled his first years in the tattoo trade.

Charlie Wagner, Bowery Tattooer. Tattoo memorabilia collection of Carmen Nyssen

—

Wagner’s First Tattoo Shops

In newspaper interviews, Wagner often claimed that New York Bowery’s celebrated “Prof.” Samuel F. O’Reilly—recipient of the very first electric tattoo machine patent in 1891—was his mentor in tattooing. Even if true, his solo education, the trial and error that comes with earning a place in the tattoo world, began in the heart of the Lower East Side. By 1899, amidst a cacophony of underground gambling dens, saloons, and brothels, Wagner had opened his earliest documented tattoo shop at 294 East Houston Street, in a building shared with Max Heimlich’s shoe & bootblack store.

Map of Charlie Wagner’s early LES tattoo shops (black dots) and residences (green dots). Modern day comparison of locations, based on early 1900s maps from the New York Public Library Digital Collection.

—

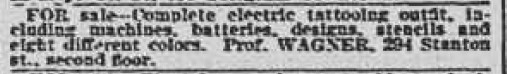

By 1901, he had moved to 294 Stanton, a few blocks away, where he began selling tattoo supplies. A 1901 advertisement indicates he was prosperous enough that he required assistance.

1901 Jan 7-The World. Pg 11: Ad: “Tattooing-Young man wanted to do tattooing by electricity, in colors Prof. Wagner 294 Stanton St.”

Charlie Wagner’s 1902 tattoo supply business. The World. 12 Apr 1902. Pg. 14

—

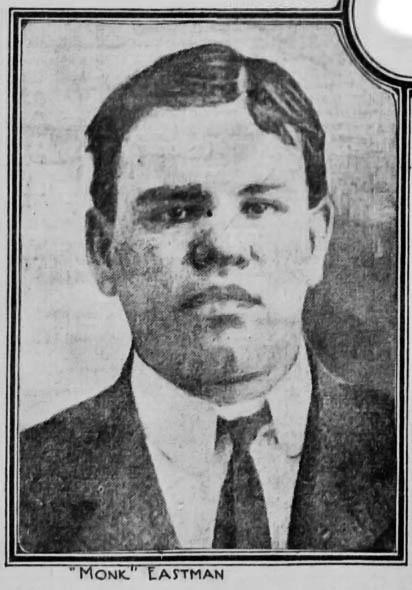

Although Wagner’s modest digs were slightly north and east of the highly trafficked shops in Chatham Square, such as those of O’Reilly at 5 Chatham Square and “Electric” Elmer Getchell at 11 Chatham Square, he built a foundation tattooing a varied clientele. At a time when the LES was stomping ground for notorious thug Monk Eastman, gangsters were no doubt among his customers, and with the Spanish American War in full swing he surely fared well tattooing sailors and soldiers.  He also had quite a following with neighborhood boys who caroused the LES streets and felt a badge of toughness on their arms was in order. An unthinkable notion by today’s standards, children getting tattooed wasn’t out of the norm in New York City, nor was it any more illegal than child labor in sweatshops. Yet, because of its ill-defined nature—in the eyes of the law and a diverse citizenry—it landed Wagner in hot water a few times in his early career.

He also had quite a following with neighborhood boys who caroused the LES streets and felt a badge of toughness on their arms was in order. An unthinkable notion by today’s standards, children getting tattooed wasn’t out of the norm in New York City, nor was it any more illegal than child labor in sweatshops. Yet, because of its ill-defined nature—in the eyes of the law and a diverse citizenry—it landed Wagner in hot water a few times in his early career.

Monk Eastman (1875-1920) gained notoriety in the late 1890s as the leader of the criminal Eastman Gang—established in New York’s LES. By 1901, his reputation had earned him the position of bouncer-thug at Irving Hall on Broome Street, in the near vicinity of Charlie Wagner’s tattoo shop(s), as well as frontman for Tammany Hall politicians. Eastman’s gang hang-out was nearby at Smith’s Silver Dollar Saloon, who was also a Tammany-supporting profiteer. As it happens, Smith was a cohort of Barney Rourke, another reigning political machine character of the LES, who operated a 35 Forsyth saloon affiliated with late 1800s tattooer Edwin Thomas). Smith’s business was located near Essex Market Court, where Wagner found himself on the trial bench for tattooing a Tammany Hall employee’s child in 1906.

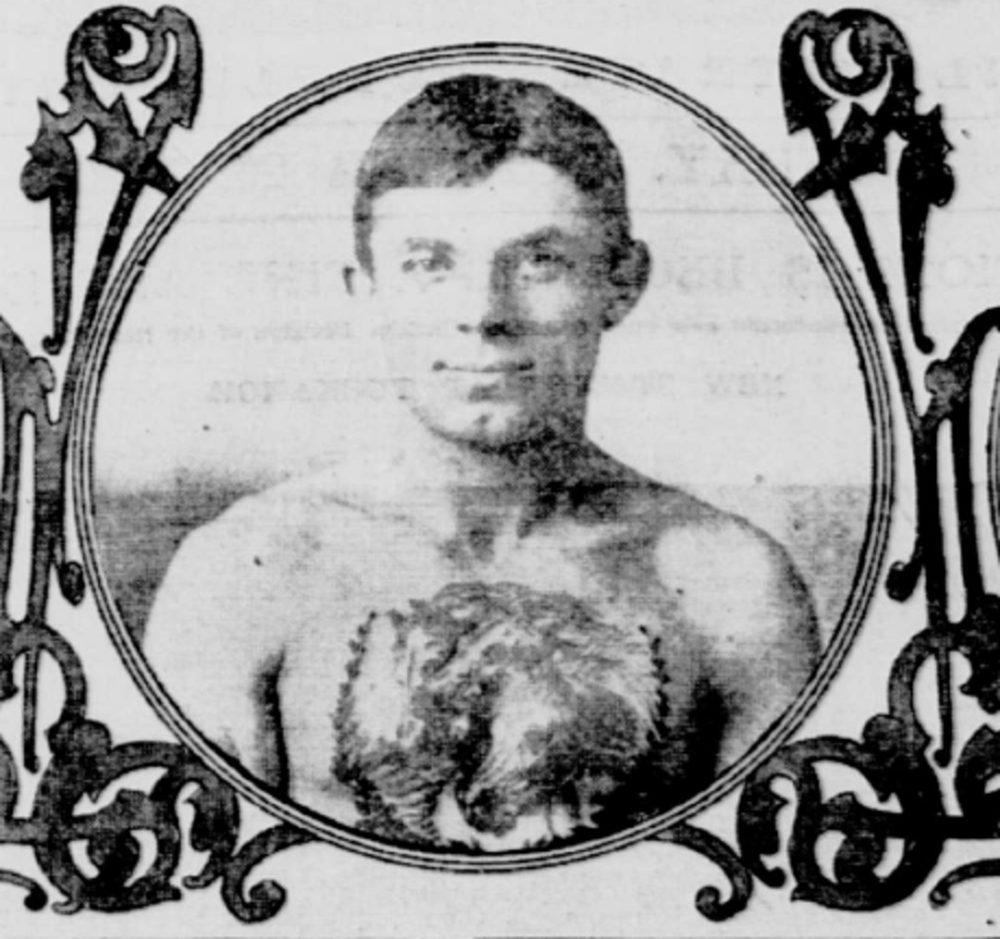

A young Charlie Wagner, before he was completely tattooed. Thanks to Jon Reiter for pointing this photo out years ago. New York Tribune Illustrated Supplement, September 1902. Wagner was 27-years-old in 1902.

Wagner’s Tattoo Trials

As reported in a New York World article, in May of 1899, at his 294 Houston shop, Wagner mistakenly inked three Jewish boys (age nine, ten, and twelve), whose families’ religious beliefs forbade tattoos. The boys, presumably coached by their parents, told policeman Wagner had forcefully put the etchings on them—the one specific law about tattooing on the books (End note 3). The case was dropped after Wagner explained that the boys had visited his shop more than once and told him their parents had no objections. While the hullabaloo undoubtedly caused Wagner professional headache, this incident, as well as Wagner’s arrests in 1902 and 1906 on authority of the Gerry Society (aka the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children), was most probably for show, to appease the moment.

Essex Market Police Court, New York City. Courtesy New York Historical Society. Location of Wagner’s 1902 & 1906 court cases.

In the last case, the court magistrate even consoled a tearful Wagner, telling him that his trial was only a test, in consideration of [flimsy] legislation that would require children [of any age] to present a parental letter of consent to get tattooed. As no new laws were instated, it seems the matter wasn’t a priority for the Gerry Society, or its close affiliate Tammany Hall—the City’s corrupt political machine that curried votes from its mostly immigrant constituents; relied on the likes of Monk Eastman for intimidation tactics; and pressured the police and courts to do their bidding (End note 4). For all the sway of this governing conglomerate, the tattooing of children remained an ambiguous, somewhat tolerated, custom in New York City for many years, and Wagner only suffered a dose of bad publicity and minor legal punishment that didn’t stifle the tattoo trade or his own career to much extent.

(Note: Silver Dollar Smith’s saloon was located right by the Essex Street Market Court).

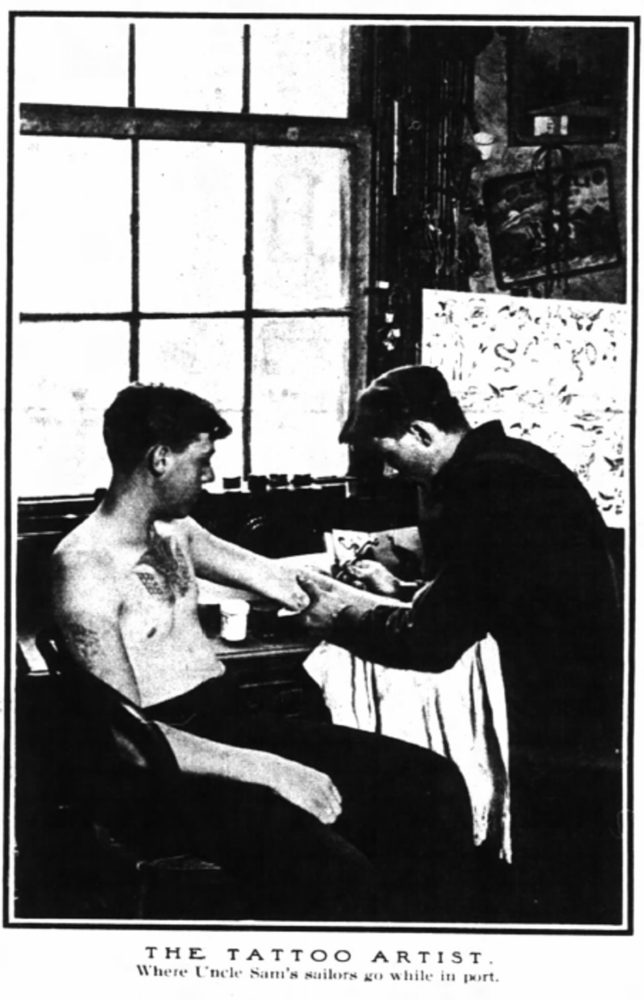

Charlie Wagner tattooing a young man in his 223 1/2 Bowery tattoo shop. New York Sun. Dec 16, 1906.

Wagner’s Tattoo Triumphs

In fact, despite some opportunistic razzing in the media from rival ‘Electric’ Elmer Getchell who called him an amateur, and being made an example of in court, Wagner was well on his way in tattooing. Sometime between April and September of 1902 he had moved his tattoo shop to 223 ½ Bowery, on the west border of the LES tenement district near the Bowery Mission, and by the time of the 1906 ordeal, had made a solid name for himself.

Tattooing Device. Charles Wagner, assignee. Patent 768413. 23 Aug. 1904. Print. It’s been said that O’Reilly helped Wagner develop his patent machine. However, Lew Alberts (real name Albert Morton Kurzman) is one of the witnesses who signed his patent. As a teen, Alberts attended the Hebrew Technical Institute in New York, where he learned a variety of skills, including metal working. School records note that he broke into the tattoo trade in 1904, the same year Wagner’s patent was issued (Hebrew Technical Institute school record found per my research).

At the 223 1/2 Bowery location, in 1904, he devised an electric tattoo machine based on a dental plugger and electric bell, and obtained the second American patent on record (likely with help from fellow LES denizen, Lew Alberts aka Albert Morton Kurzman, who had studied drawing and metal-working at the Hebrew Technical Institute and signed as a witness on the patent).

In addition to his ongoing tattoo machine innovation and his continued operation of a tattoo supply business throughout these early years, Wagner fostered a reputation as a preferred artist for would-be tattooed attractions—a good number of them boys, no less, who went on to have fruitful careers trouping with sideshows and tattooing.

—

223 1/2 Bowery

Photo of where Charlie Wagners c. 1902-1909 223 1/2 Bowery tattoo shop was once located (c. 1915, 6 years later).

2nd shopfront from the left with the words “clothing” on the awning.

Wagner’s Tattooed Troupers

As a sampling of Wagner’s all-over tattoo work, one of numerous youngsters he made exhibit-ready was Andrew John Stuertz (1892-1962). Orphaned in 1901 at age nine, and raised by his mother’s family in Philadelphia, Stuertz had trekked to New York City by the time he was sixteen-years-old and had Wagner decorate him from head-to-toe. He enjoyed an over 50-year-long career in the tattoo business.

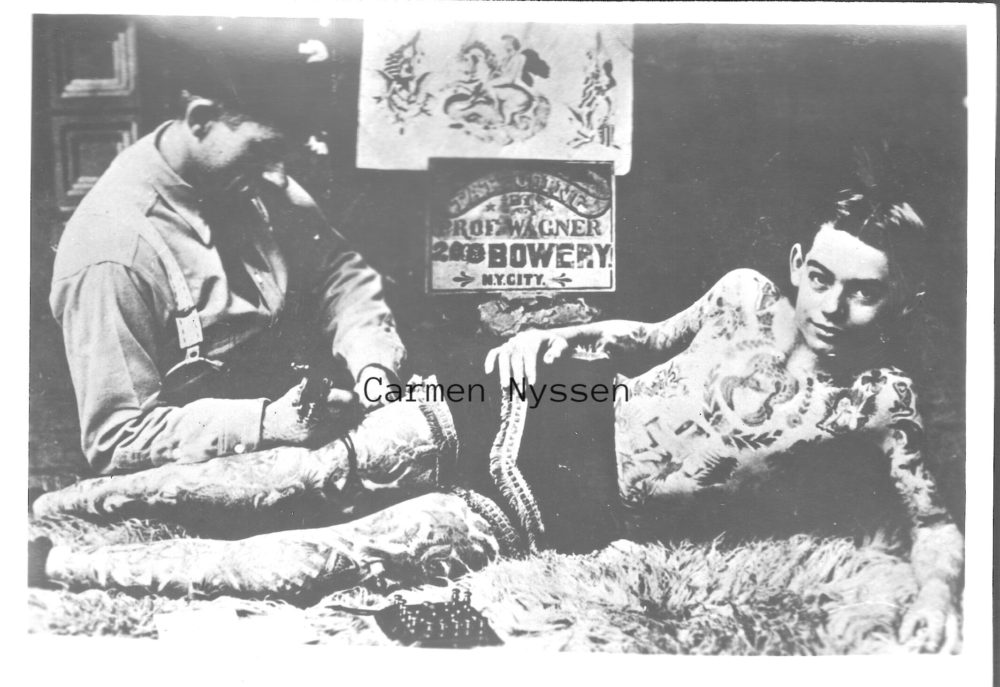

Bowery Tattooer, Charlie Wagner, tattooing a teenage Andy Stuertz. Tattoo memorabilia collection of Carmen Nyssen. Wagner likely sold prints of this image. The sign in the original version of this photo noted “223 1/2 Bowery.” The wording on the sign was written over for this version to state “208 Bowery,” perhaps to promote Wagner’s tattoo factory/shop at this location.

1908 July 11 New York Clipper

Gollmar Bros. Circus

“Master Andrew Stuertz the youngest tattooed person in the world, being tattooed from head to toe in beautifully colored designs”

—

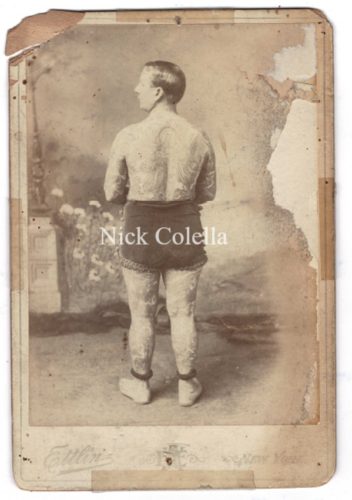

Young boys with spectacular bodysuits no doubt stood out from aged adult attractions, but Wagner wasn’t discriminate. At this shop, he tattooed Barnum’s future tattooed man, Edward Greenwood, then in his late 30s (born c. March 1866).

Edward Greenwood, tattooed by Charlie Wagner & Lew Alberts. Tattoo memorabilia collection of Nick Colella.

—

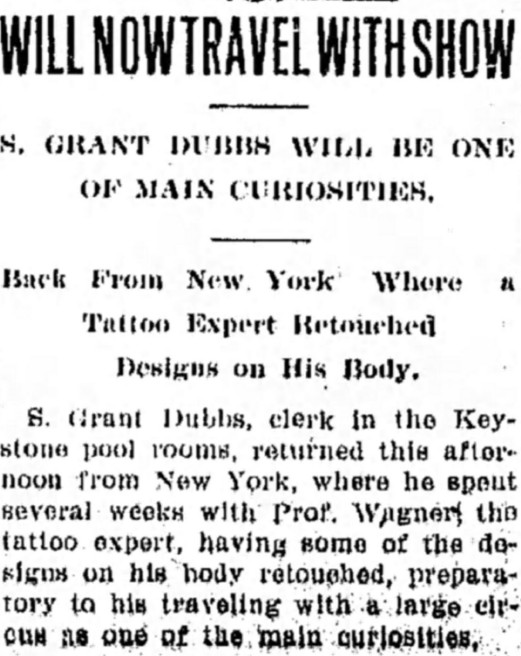

And he re-worked the designs of a previously tattooed attraction Grant “Shorty” Dubbs (1869-1942), a poolroom clerk also in his late 30s, who traveled all the way from Lebanon, Pennsylvania for the treatment.

Lebanon Daily News. 27 June 1905. Pg. 1.

—

Note: Wagner’s friends, particularly Lew Alberts, often had a hand in some of his early tattooed creations.

Wagner’s Tattoo Legacy

By the time of Samuel O’Reilly’s unfortunate death on April 29, 1909 (he fell off a ladder while painting his Brooklyn home), Wagner was primed to fill the shoes of his alleged mentor. Soon after, he traded his Lower East Side shop for O’Reilly’s coveted spot, then at 11 Chatham Square (End note 5), and within several years founded ‘Chatham Electric Tattooing,’ a multi-location tattoo shop-supply enterprise that continued growing into the 1920s. (End note 6). Throughout the years, he tattooed many and passed on his knowledge in the craft. Ultimately claiming his place as ‘King of Bowery Tattooers,’ he was featured extensively in newspaper and magazine articles, and even secured a radio interview with Fred Allen in 1938, and another on “We, The People,” in 1941. At the height of his career, he was known world-wide.

This subsequent period wasn’t free of difficulties, however. In 1920 and 1928, Wagner had to recover from fires that completely destroyed two of his locations, and in 1929, he lost his hard-earned wealth in the stock market crash. During the ensuing Depression, he was forced to lower the prices of his tattoos to 25¢ and 50¢; it was said that he lived much like the homeless Bowery bums, bedding in flophouses and going without a meal until tattooing his first customer of the day. When the Depression ended in the late 1930s, the sixty-something-year-old Wagner had conceded to a more basic existence, and his business never reached the same level of success as in his heyday. Still, for better or worse, he persisted in the tattoo trade—and on the Bowery—as the renowned Charlie Wagner up to his last days. He was a true New York City character, enmeshed in a unique and diverse landscape and its less than straightforward ways.

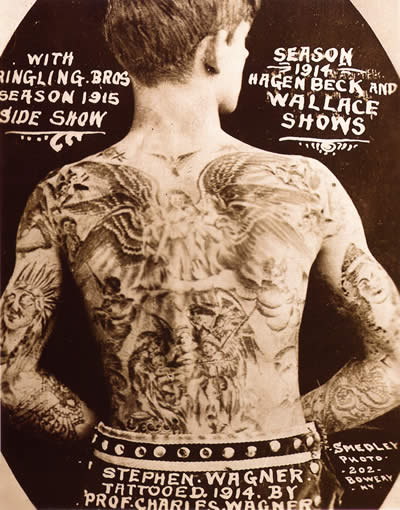

Stephen Wagner

A person often forgotten in the story of Charlie Wagner’s enduring legacy is his half-brother Stephen Wagner (1897-1975), born to his father Edward and his stepmother Catherine Dammick (spelled with numerous variations) (1870-1907).

Stephen Wagner, tattooed man and half-brother of Bowery tattooer, Charlie Wagner. Photo from unknown internet source.

—

By 1914, after moving to Chatham Square, Wagner had covered Stephen in a beautiful body suit and set him up for a lucrative career as a tattooed man. Stephen soon after joined the Hagenbeck Wallace Shows and Ringling Bros. Circus. In 1918, he was on display as the “Tattooed Adonis” at Coney Island’s Dreamland Circus Sideshow. As noted on a passenger manifest and passport application, he also made appearances in Cuba in 1917 and 1919. Stephen tattooed for quite a while longer, but according to family lore, was finally forced out the trade by his wife when she caught him tattooing a woman’s breast in his Surf Avenue shop on Coney Island (last tidbit per passed on family history of grandson Keith Wagner).

Charlie Wagner’s brother, Stephen Wagner, with Coney Island, Dreamland Circus Sideshow. Billboard Magazine. 22 June 1918. Pg. 37

End Notes:

1)-In regards to documentation of Charlie Wagner’s death date, Tattoo Archive notes about the “International Tattoo Club” state: “In was in that newsletter that the death of Charlie Wagner on January 1, 1953 and of Percy Waters in December, 1952 was announced.” Unfortunately, if there was a notice citing his exact date of death in newspapers or private paperwork it has yet to surface. The best supporting documentation is included in a letter from Owen Jensen to the Peace family, which is dated July 12, 1953 and states that Wagner had died “quite some time ago” (Peace family collection). Death records are available at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, but access to records from 1949 to present are strictly regulated and you must know the exact date of death. Their index listings below are the closest matches for Wagner:

Charles Wagner: b. abt 1871 26 Jun 1952 Brooklyn

Charles Wagner: b. abt 1872 27 Jan 1953 Brooklyn

Charles Wagner: b. abt 1873 9 Apr 1952 Manhattan (this person is buried in Greenwood Cemetery-high research fees for genealogy)

Charles Wagner: b. abt 1890 29 Oct 1952 Manhattan

Tattoo lore also states that Wagner was buried in New York City’s Potter’s Field. This is likely the case. Most of his family is buried in the Lutheran Cemetery in Queens. The cemetery thoroughly checked their files and did not find a burial record for Wagner under any name variation.

A Potter’s Field record for Wagner may or may not be available in the New York City Municipal Archives: “Burial records from prior to 1977 are held by the Municipal Archives (LINK), except for those records that were destroyed in a fire in the late 1970s, including records from between 1956 and 1960 and several years of records during the 1970s.”

2)-The Wiegner family is documented in Prešov Evangelical Lutheran Church records (they were not Jewish as has been recorded previously). Although there’s a break in birth/baptismal records for the time of Wagner’s birth (restarts in 1876), his family—his father, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, as well as his younger siblings—are documented in Prešov Lutheran Church ledgers. Vital records for his immediate family in New York cross-check with these records (they continued using the Wiegner spelling for some time). Wagner’s father was married several times and had many children, though unfortunately with the high mortality rate of the era, only Wagner, his sisters Mamie and Catherine, and his half-brother Stephen survived to adulthood. Wagner’s mother died on April 07, 1890 in Manhattan and his father married two more times—separated from his second wife and widowed by his third. Wagner’s date of birth is documented by his World War I Draft card, under the name Charles Wiegner.

**It was my pleasure to share my indepth genealogical research, with the above documentation, to Keith Wagner, grandson of Stephen Wagner, and his family. Genealogy sources are too extensive to list here.

**Also see my Find-A-Grave Memorials for my Wagner/Wiegner family research. Although I’ve since relinquished my account, the information is still listed on the memorial(s).

3)-The only law(s) concerning tattooing in New York City for many years:

A Digest of New York Statutes and Reports by Austin Abbott pg. 227. “Maiming: 1. Statute. Tattooing or disfigurement resulting from hazing, prohibited. L. 1894. P. 482, c. 265.”

The Revised Statutes, Codes and General Laws of the State of New York 1896 pg. 1404: “L. 1894, c. 265, § 1. 2 Tattooing, etc.; punishment of crime. Whenever any tattooing or permanent disfigurement of the body, limbs or features of any person or persons may- result from such hazing, by the use of nitrate of silver or any like substance, it shall be held to be a crime of the degree of mayhem, and any person guilty of the same shall, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment for not less than fifteen years. Ld., 2. See also Injuries; Malicious Mischief”

In 1902, Wagner had tattooed another young Jewish boy, this time with a crucifix (another unnamed tattooer had also been incriminated for tattooing young boys). His scapegoat tall tale was that he had perfected such designs while working in London and Spain and didn’t realize their significance when tattooed on a Jewish person. He was let off with only a severe reprimand from the judge on the promise that he wouldn’t tattoo anymore children.

In the 1906 case, Wagner was convicted and sentenced to twenty days in jail for imperiling the life of a minor, Section 289 of the penal code. Though there were supposedly numerous complaints from citizens about the tattooing of children, the main minor in question, Danny Spurdetto, was the son of Tammany Hall supporter Frank Spurdetto of 70 Mott Street (also the bootblack at Tammany Hall). A couple newspaper reports allude to Wagner having caused actual health injuries to children. The notes of the court case, however, only mention a potential danger and name the young Spurdetto as being “disfigured” or “subject to blood poisoning,” the most fitting legal assessment in favor of the complainants (Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, Volume 12-By New York (State). Legislature. Pg. 36)

Section 289, New York Penal Code: “A person who, having the care or custody of a minor, willfully causes or permits the minor’s life to be endangered or its health to be injured –is guilt of a misdemeanor.”

Only several months later, in September, three Chatham Square tattooers, Sam O’Reilly, William R. Davis, and Peter Farley, were arrested for tattooing a 15-year-old “waif of the Bowery,” Madeline Altman.

4)-Immigrant constituents were staunch supporters of Tammany Hall. Whatever the motives, Tammany offered many charitable programs for the poor. Even such characters as Silver Dollar Smith, who used his saloon as a front for underhanded political dealings and employed Monk Eastman as a henchman, was a beloved benefactor of immigrants in the Lower East Side. It was simply too different a time and environment to pass judgement on from our modern viewpoint.

5)-As per my research in historical records, Sam O’Reilly had moved from 5 Chatham Square and taken over Elmer Getchell’s 11 Chatham Square tattoo shop when Getchell left New York c. 1904.

6)-Although 11 Chatham Square was Wagner’s main tattoo shop from 1909, he was located at several different shops throughout his career. During the Depression he was located at 16 Bowery with Joe Van Hart a short while (see my Willy Moskowitz Bowery-Barber Tattooer research article), and in much earlier years, at various locations listed in the Buzzworthy Tattoo History feature, Charlie Wagner’s ‘Chatham Electric Tattooing’ Enterprise.

Articles/Sources:

Genealogy research of Carmen Nyssen: see end note 1 and 2.

“Tattooed East Side Boys.” The World, 28 May 1899, p. 14.

Advertisement. The World, 7 Jan. 1901, p. 11

Advertisement. New York Telegram, 12 Apr. 1902, pg. 14

“Crucifix on Hebrew.” Daily Review, 28 Sep. 1902, p. 1

“Tattooed Children Astonished Teachers.” Los Angeles Times, 1 Nov. 1902, p. 4

“Will Now Travel With Show.” Lebanon Daily News, 27 Jun. 1905, p. 1

“King of Tattooers Jailed.” New York Times, 27 Jul. 1906, p. 14

“To Jail for Tattooing Danny.” New York Sun, 27 Jul. 1906, p. 6

“Girl Wants to be a Sailor.” New York Times, 15 Sep. 1906.

Charles Wagner court case summary. Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, By New York (State). Legislature. Assembly. Vol. 12, ser. 32-41, J.B. Lyon & Co., 1907.

“Gollmar Bros. Circus.” New York Clipper, 11 Jul. 1908.

Stephen Wagner passenger manifest. Year: 1917; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 2516; Line: 5; Page Number: 136

“United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” Charles Wiegner, 1917-1918; citing New York City no 95, New York, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.)

Advertisement. Billboard Magazine, 22 Jul. 1918, p. 37.

Stephen Wagner passport application. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 955; Volume #: Roll 0955 – Certificates: 129126-129499, 16 Oct 1919-17 Oct 1919

Publications:

Willy Moskowitz: Bowery-Barber Tattoo Artist. In the Shadows: The People’s History of New York City Underground Tattooing. Tribal Publishing, 2023. Print. Authored by Carmen Forquer Nyssen. (2nd full feature article, after introduction, in this 600 page groundbreaking anthology of New York Tattoo History). (Includes historical context for Charlie Wagner’s tenure on the Bowery & other tattooers)

A Life in Tattoos: Henk Schiffmacher’s Private Collection of the Art and its Makers, 1730s-1970s. By Henk Schiffmacher, Noel Daniel. 2020. Print. Research, consultation, and fact-checking.

Acknowledgements: “To Carmen Forquer Nyssen of the Buzzworthy Tattoo History Website for the enlightenment her research provided into early American tattoo history, early electrical tattooing, Charlie Wagner and his contemporaries, and her great great uncle, Bert Grimm.”

Buzzworthy Tattoo History research essays related to Charlie Wagner:

Charlie Wagner’s ‘Chatham Electric Tattooing’ Enterprise

Wagner, Tattooer, Quips With Fred Allen

New York Tattoo Shops at 5 & 11 Chatham Square

Early Tinkerers of Electric Tattooing

Battleship Kate, New York City’s Tattooed Sailor Groupie

Willie Moskowitz Bowery Barber-Tattoo Artist

Also see: “Lew The Jew” Alberts, a Hardy Marks publication, featuring original biographical research/content by Carmen Forquer Nyssen